Back at the beginning of 2013, we ran a story about Anime! Real vs. Dream, a book on the state of the anime industry written by insiders at Studio Madhouse. What kind of insights lie inside? Let’s take a look.

Anime! Real vs. Dream is aimed at middle and high school students who harbor dreams of entering the anime industry or simply want to know a little more about the creation process and business realities of their favorite cartoons.

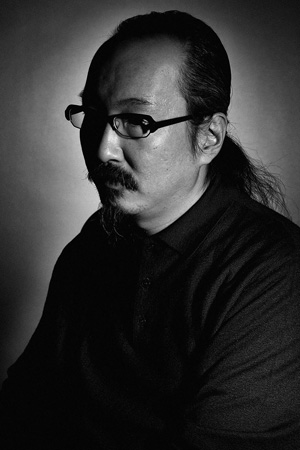

This journey through the anime industry is presented as a back-and-forth discussion between new Madhouse president Hiroyuki “Hiro” Okada and PR chief Fuuta Takei. Hiro, who became president after Nippon Television’s purchase of the company in 2011, makes no qualms about his near-total lack of anime knowledge, having worked primarily as a producer at NTV for most of his career.

Fuuta, on the other hand, acts as the voice of otaku reason (or lack thereof), and is a font of knowledge about anime history, moe, and why anyone in their right mind would pay $800 for a DVD box set.

Most of the first third of the book or so is dedicated to figuring out how the anime industry ended up the way it is today. Fuuta pinpoints Evangelion as the catalyst for what eventually became the modern industry business model of creating shows that exist as advertisements for their home video release. Eva didn’t just change the perception of anime in the public consciousness, it also sold 1.5 million copies on laserdisc alone, opened the floodgates on shows geared towards otaku, and was instrumental in creating a concept Fuuta refers to as “My Anime”: niche shows with early-morning TV timeslots that shoot to make their money back on home video sales.

This period also saw the rise of production committees as a means to finance anime, splitting the risk up among a large number of investors, including some — like financial institutions, banks, and so on — who never would have been involved in anime production before this point.

Moe Better Blues

Moe Better Blues

And then they broach the subject of moe. Where the heck did it come from? Fuuta suggests 1998’s Cardcaptor Sakura was the point at which moe became a Thing in the hearts and minds of anime fans, a phenomenon that only intensified as the shift to late night and “My Anime” continued throughout the 2000s. Hiro has to ask: what is moe, exactly? Fuuta answers “there’s no set definition or even accepted premises for what moe is, but that vagueness allows fans to find their own personal definition of moe and go with it.”

Thanks.

When Hiro points out this trend towards a otaku-only subject matter that the fans themselves can’t even define makes anime in general harder to approach and get into, Fuuta points to the industry catch-22: it sells. And if a show somehow gets branded as being not moe? Good luck making your money back.

“But wait,” Hiro asks, “what about movies like Spirited Away and other properties that make no appeals to the moe-otaku fanbase?” Fuuta has to be blunt: that stuff isn’t even really part of the same discussion, because the market for anime targeted at otaku audiences is so insular that nobody outside of that small circle is going to pay for the Blu-ray.

Less Money, Mo’ Problems

Chapter 6 is titled “The Anime Dilemma.” When the subject of wages in the industry comes up, Hiro and Fuuta don’t shy away from the poverty facing most animators:

Hiro: “How many key frames can a single artist draw in a day?”

Fuuta: “Well, it depends on what they’re drawing, but typically 15.”

Hiro: “How much do they get paid per drawing?”

Fuuta: “If they’re working on a TV show, a little more than 300 yen.”

Hiro: “So 15 images at 300 yen each… Wait, that’s barely more than what you’d get working at a fast food place!”

Fuuta: “You really have to love the work.”

We’ve been hearing about the low pay and poor working conditions in the industry for years and years now. That’s not new information, right?

What is new information, at least to me, is the revelation that the workforce in anime production is increasingly skewed towards women, a major shift in a traditionally male-dominated industry. Hiro points out that in the past 3 years, out of the 15 contract hires Madhouse brought on to help with animation work, only one was male.

“5 of the recent female hires we brought on were promoted to key animation not too long ago,” says Hiro. “I don’t know what we’d do without them.”

Hiro mentions a new subgroup within Madhouse called MadchenHeim, which will put the female creators and animators at Madhouse in charge of new projects, but offers few details and — as of this writing — there’s still no information anywhere online about the group.

Also interesting is a discussion on recent shifts in how the anime industry outsources grunt work overseas, with China supplanting Korea as the go-to source for ultra-cheap animation labor. Coloring work can be done in China for half of what you’d pay an animator in Japan, and they work digitally, making for an easy transfer of materials.

Hiro floats the question of why they don’t try to market anime more in China, beyond occasional projects like 2011’s Tibetan Dog Story, which was a co-production between Madhouse, China Film Group Corporation and Ciwen Pictures. Beyond the classic issue of piracy, there’s also two other major hurdles standing in the way, according to Fuuta: censorship, and the inability for many Chinese viewers to access the original source material (manga, light novels, etc.) that many anime are based on. Until those barriers are lowered, China will remain a difficult market to sell to.

Bubble Crisis

Chapter 8 is titled “Real Business.” It lives up to the name, delving into some of the raw figures of the industry, with Hiro focusing particularly on the “Anime Bubble” that started in 1998 and peaked in 2006 with a staggering 276 titles produced.

What started the bubble? First, 1998 saw WOWOW, a satellite TV station in Japan, begin to air free anime in their traditionally pay-per-view broadcast schedule. In October, they aired Cowboy Bebop, which ended up being popular enough to inspire other satellite networks to pursue anime productions. The result: more anime programming, with riskier content than you’d see on traditional, non-satellite networks.

But the biggest factor in creating that bubble was the influx of financial institutions and corporations suddenly getting into anime production during the late 1990s and early 2000s in the pursuit of what they saw as mass worldwide popularity of shows like Pokemon. Frequently, these investments were made with little to no research into what they were actually helping to fund, and the end result was pretty much what you’d expect: a market glutted with content to the point of unsustainability.

Fuuta and Hiro are both very upfront about how far things have come down from the mid-2000s. Current yearly production at Madhouse is an even six titles, down from nearly double that at the height of the bubble. What did they learn from those heady boom times? One, you can’t really support that many shows without going into the red, and two, to be careful of the character goods market — nobody’s going to want to buy figures and other merchandise if they don’t like the show.

Fuuta busts out some statistics to illustrate the collapse in rentals/sales of DVDs and Blu-rays, which held steady at about 700 billion yen per year up until 2008. In 2006, 8.6% of consumers of anime DVDs were considered “heavy buyers,” who spent more than 30,000 yen a year on discs. By 2011, however, that figure had dropped to a mere 3.6%. Clearly, the market’s changed, which is why everyone in the industry’s been cutting back on production.

Well, almost everyone. Fuuta cites Toei Animation, for example, as still doing gangbusters even in the post-animepocalypse of 2013. They have the biggest hits in the business with One Piece and Pretty Cure, and they also have divisions dedicated solely to making their products more marketable, both domestically and overseas.

They’re an outlier. The rest of the industry, Hiro says, is going through a massive restructuring. Most of the studios in the industry have been forced to become child companies of larger corporations, Madhouse included — they came under the umbrella of Nihon TV a few years ago. Oh, sure, there are a few holdouts. Production IG, Tokyo Animation and a few other companies have all remained independent even in light of the upheaval in the marketplace, but Fuuta has a hard time grasping how they’ve managed to stay afloat: “They’re all stealing from the same pie,” he says.

Hiro even goes so far as to say most people working in anime are simply not good at business: they’re easily taken advantage of and don’t fight for what they deserve in negotiations. Fuuta has a hard time denying this. It’s just another reason why the anime industry’s been having a hard time staying above water.

If all of this sounds a little disheartening, well… it kind of is, isn’t it? Hiro and Fuuta refuse to end on a bleak note, though. Yes, people who work in the industry might be easily used by others and have a hard time turning down requests, but they’re also fighting for a dream they believe in. They’re doing this not because of the money, or the fame, or the prestige and respect of their peers, but because they love animation.

Hiro then asks if it’s fair to group anime fans into the same moe otaku stereotype, and Fuuta protests. Yes, hardcore anime fandom has an image of being a closed off community, but Fuuta insists that it’s far more open and welcoming than it appears, even if most “normal” people would never think to visit Comic Market or similar otaku-centric events, and urges people to “give it a shot!” and seeing firsthand how welcoming the community is. He even goes so far as to compare it to raising Bonsai, which gets Hiro thinking. Perhaps anime fans aren’t at war with reality, so much as trying to maintain peace and harmony through their love of a shared subculture? Perhaps.

Unfinished Dreams

The subject turns, suddenly, to the topic of the late Satoshi Kon, director of Paprika, Tokyo Godfathers, and the unfinished Dreaming Machine. The film’s production has been stalled, and Hiro reveals the issue isn’t lack of funding so much as an inability to replace Kon himself as director.

The subject turns, suddenly, to the topic of the late Satoshi Kon, director of Paprika, Tokyo Godfathers, and the unfinished Dreaming Machine. The film’s production has been stalled, and Hiro reveals the issue isn’t lack of funding so much as an inability to replace Kon himself as director.

“We assembled the same staff that worked on his previous films, and completed the shots according to what Kon left behind, but… something was missing,” says Hiro. “Something spiritual. The unyielding will of the director to see his vision through to completion.”

So they’re going to wait. Not just for funding, but for the day when a director with the talent and vision to finish Kon’s vision appears.

The book ends with a final comment on the title of the book, on the conflict between the dream and reality of anime production. “I want to see my dream of finishing Kon’s last film become a reality, and I want to see the reality of making anime improve for everyone involved.”

This story originally ran in the 10/15/13 issue of the Otaku USA e-News

e-mail newsletter. If you’re not on the mailing list, then you’re reading it late!

Click here to join.

More animator stories:

– Newbie Animator Hourly Wage: Around One Dollar

– An American Animator in Tokyo

– Miyazaki Blames Otaku Animators for Anime Decline

– Takahiko Abiru Interview

– Shirobako’s Real-life Counterparts