Ken Sugimori is a cool dude. You might think the guy who helped co-create Pokemon would be a little arrogant, spending his days in some kind of ivory tower, sleeping on top of large piles of money, and generally being a media gadfly. But if there’s anything I learned after reading Ken Sugimori Works, a recently published book looking at the career of the guy who originally designed Pikachu, it’s that Sugimori is incredibly humble, talented, and probably someone you’d want to grab a beer with. Also, he likes Robocop a lot. Maybe too much.

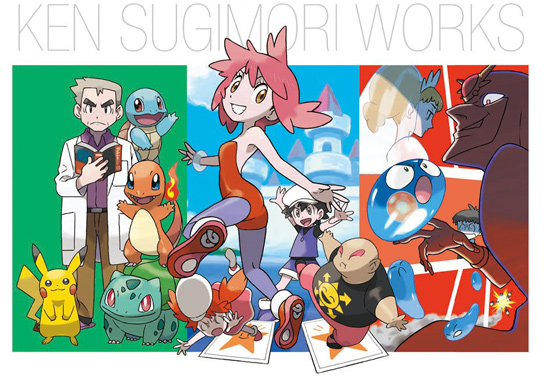

Coming in at a stout 358 pages, the book is a great look at the less publicized-side of the man who designed the original 151 Pokemon. There seems to be a tacit understanding from the editors of this thing that really, the world doesn’t need another book full of Pokemon artwork: the multimedia juggernaut that put developer Game Freak on the map has a scant 15 pages devoted to it.

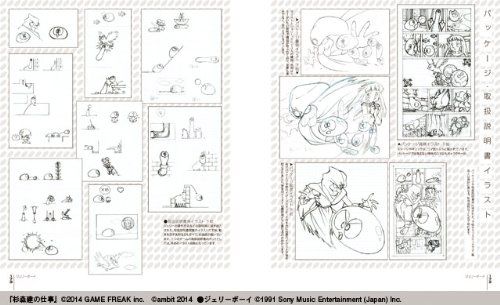

What rounds out the pages in its stead is much more interesting. There are original development and planning materials from Quinty, Jerry Boy (released in the US as Mendel’s Palace and Smart Ball, respectively) and other lesser-known titles Game Freak worked on before hitting it big in the mid-90s. There are pages from a TV drama adaptation Sugimori worked on during his brief stint as a “serious” manga artist, covers from a Sega fanzine he helped out with illustrations on (despite being partly responsible for the most successful third-party Nintendo franchise in history, Sugimori’s not-secretly a giant Sega fanboy), and a smattering of 4-panel comics that appeared in strategy guides and fanzines.

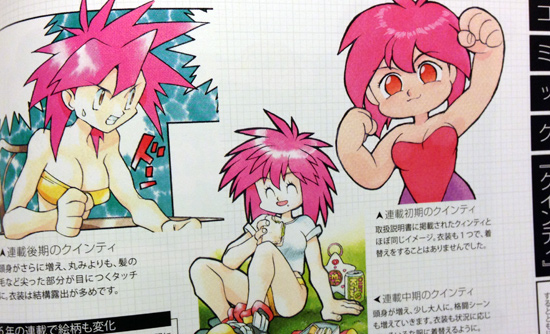

About 130 pages are dedicated to a never-before-reprinted compilation of all 56-some chapters of the Quinty manga, which ran from 1990 to 1995 in the pages of game magazine Famicom Hisshoubon.

It’s light, goofy, gag-comic fare — fiery red-head Quinty wears skimpy outfits, uses her super powers to cause trouble for her brother Carton and his girlfriend, and generally engages in Wacky Hijinx — but what’s more immediately interesting here is the staggering evolution in Sugimori’s art style over the course of those 5 years. Characters begin as squat, cherubic blobs, evolving over time into the kinds of human character designs you see in Pokemon, with tall, lanky proportions and hair that’s all sharp angles, a complete 180 from the starting point.

Caption: Believe it or not, these are all supposed to be the same character.

Caption: Believe it or not, these are all supposed to be the same character.There’s also a reprinting of the inoffensive comic version of Jerry Boy, which like everything else in the book looks great blown up to the book’s fairly jumbo 8.2 x 7.2 dimensions. It’s nothing special, but if you like Sugimori’s art style — or just early 90s manga sensibilities in general — you’ll dig it.

Scattered throughout the book are interview segments between Sugimori and long-time Game Freak collaborator and friend Tomisawa Akihito, in which they discuss Sugimori’s youth, inspirations, and a few of his favorite things. Here are a few translated excerpts from the full thing:

Sugimori grew up in a house filled with manga his NHK radio-producer dad bought: Star of the Giants, Tezuka stuff (Dororo et al), various other lesser-known titles. Sugimori figures that’s probably where his interest in manga started. Other influences on him were Mitsuru Adachi’s Hirahira-kun Seishun Jingi, the works of Cyborg 009 creator Shotaro Ishinomori and the 4-panel comics that appeared in the Mainichi Shougakusei Shinbun.

Realized he loved manga and anime around 3rd or 4th grade after he started to really get into Mazinger Z — has distinct memories of getting caught up in the toys, stuff like Getter Robo, Super Alloy Z gimmick etc. Like many kids his age, he was amazed by Yamato, and recalls thinking the top-half of the Yamato with all the lines and details was so cool. Big contrast with how real it felt in comparison to Mazinger and the other cartoon heroes of the era.

The first “serious” manga he made (by splitting a notebook in two to get it closer to tankobon size) was a Yamato manga, which he made his classmates read. He and his friends also wrote “relay manga” where they traded off drawing pages. They continued this tradition all the way up to high school graduation, and they hit 50-some volumes total. He and his friends were hugely influenced by the works of Yoshiyuki Tomino: shows like Gundam and Space Runaway Ideon were visible influences in the pages of their manga.

Sugimori’s first encounter with games, which would shape the rest of his life in ways he could never imagine, happened in the 1st year of middle school. A friend of his who was kind of a bad apple took him in secret to a game cafe that had sit-down Space Invader machines, but he didn’t really enjoy the atmosphere much — he was kind of a serious, studious kid who didn’t want to do anything wrong (something that hasn’t changed much in adulthood, Tomisawa notes), and felt bad about the whole experience.

It wasn’t until a plastic model shop near his house got some Galaxian mini-cabs that he really fell in love with games and thought “whoa, these are fun!”

Didn’t have any inkling that it would be possible to pursue games as a career, and wanted to become an animator rather than a manga artist when he was a kid. There wasn’t a lot of info about how games were made, while anime seemed obvious: you just have to draw stuff on the page! A lot of magazines had behind-the-scenes features on how anime was made, but even as a kid Sugimori was aware of how hard it was to be an animator and make a living. He tried drawing animations on his own and realized it wasn’t really for him when he was in high school.

One of his classmates (Muneo Saitou) won a best newcomer manga artist award after debuting in Shounen Sunday Magazine, which inspired Sugimori to do the same. Influences at the time were guys like Masami Yuuki (creator of Mobile Police Patlabor and Birdy the Mighty). Anime-styled love comedies were really popular at the time, and Sugimori was a big fan of Urusei Yatsura, so he submitted something along those lines when he was debuting in Sunday.

After graduating high school, he left home on his own and ended up living something like 10 feet away from future Game Freak founder Satoshi Tajiri.

He’d already met Tajiri at an amusement machine show back in high school and got involved with the creation of the Game Freak fanzine, which at the time was a simple thing that they pieced together by hand and sold for 200 yen.

At the time, Sugimori didn’t have any long term goals and was whiling away his days playing games and working part-time dead-end jobs. He managed to get a couple things published in Shonen Sunday Magazine, and ended up working on a fairly long running comic adaptation of a TV Drama series called Shin Maido Osawagaseshimasu before he getting sucked into working on Game Freak’s first game: Quinty.

He didn’t think they’d be able to get a full-on real-deal Famicom game made with a cartridge and everything (nobody as small as they were had ever done anything like that before), but it was originally presented to him as a PC game, so he figured they’d be able to do something at the very least. Had confidence in his pixel art skills, too.

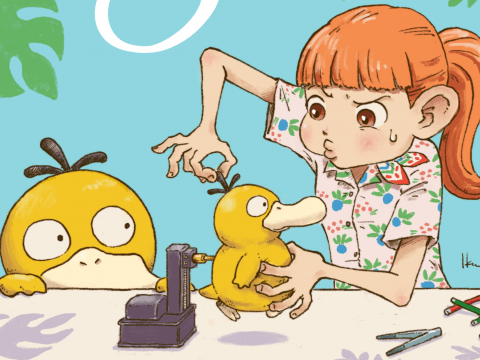

What was it like working on Quinty? “It was fun. Really fun.” If he saw something in the game that he thought could look better, it was easy to just go and make it look better right there. Tomisawa recalls poking his head into the Game Freak “offices” at the time and clearly remembers seeing Sugimori redrawing the Ballerina’s animations over and over again. Sugimori doesn’t think he’d be able to enjoy it that much now, but at the time he was completely sucked into the process (and it’s not like they had much of a choice, anyway) — they just all wanted to see the thing released. Ah, youth. And of course Sugimori’s position as kind of a freelance artist on the thing wasn’t too rough.

Sugimori continued working as a manga artist drawing serialized story versions of Quinty and Jerry Boy before finally deciding to become a proper employee at Game Freak. It happened about 2 years after Game Freak had officially become a company, and Tajiri, the founder, asked him to come onboard. From there, Sugimori handled more than just art, taking on design and directorial duties for a few games, including Magical Taluluto-kun, a Genesis game based on a popular Shonen Jump manga series.

When pressed about it, Sugimori can’t quite remember exactly why he ended up in those roles, beyond Tajiri asking “hey, can you give this a shot?” Had a lot of requests from Sega, including some for a sequel to Phantasy Star and a character game using a certain fast food chain’s mascot character — which, whoa, is this what ended up becoming McDonald’s Treasure Land Adventure?

They ultimately settled on Magical Taluluto-kun, and Tomisawa remembers expressing doubts about making licensed games to Tajiri and getting yelled at: “Do you have any idea how hard it was to get this contract?!”

Even though it was a licensed game, they put everything they had into it. At the time there were a lot of bad licensed games made by developers who clearly just didn’t really care about what they were doing, but the team at Game Freak tried their best to make a game that lived up to the source material. The core game mechanic (using one of the main character’s magical items to infuse inanimate objects with a smiley face and turn them into weapons) came directly from a chapter in the comic, and they made sure to get the voice actor of the main character from the TV anime to voice the character in-game, too. And sing-songily say “Sega!” on the title screen, of course.

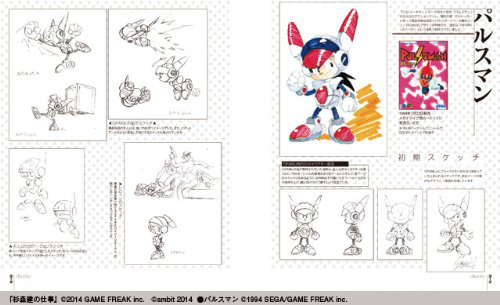

Their next game was Pulseman for the Genesis in 1994, which Tomisawa comments never seemed to be Sugimori’s kinda game. Turns out the game’s setting was handled by other staff members, but Sugimori was responsible for the game’s overarching design and made something that reflected his own personal tendencies.

That ended up being the last game he worked on as a director for many years, until Screw Breaker (released in the US as Drill Dozer) for the Game Boy Advance in 2005. After working on Pokemon for all those years, Sugimori really wanted to work on something original from the ground up. Sugimori had received a lot of praise for his work on Pokemon, so on some level he wanted to earn similar praise for something he made from square one. ”I mean, that’s the simplest way of putting it, but in the end I had to learn firsthand that what I wanted wasn’t really that important.” (laughs)

Tomisawa notes a lot of people really dug Screw Breaker even though it didn’t do Pokemon numbers, but Sugimori feels like they didn’t have a good sales strategy for the game, especially for a fairly serious action game like that. Either way, Sugimori has no regrets about how Screw Breaker turned out. He wasn’t too happy with Pulseman, but Screw Breaker was, in his eyes, a success.

Sugimori says he’s still interested in the idea of directing or designing a never game, but wouldn’t want to steal opportunities away from younger staff, preferring a support role helping out next generation of designers.

When asked about whether he has to delegate work to staff now that Game Freak’s expanded so much, he says for the most part, no. Even though some of the non-Pokemon characters are handled by others, he still draws all the illustrations for the official guide books himself.

It’s been that way since the very first Pokemon strategy guide, which was a mere 140 pages. All the Pokemon were just pixel art at the time, so he had to redraw them all in full size.

Going back a bit, Tomisawa asks if there was ever a moment when Sugimori felt like “man, I’m really good at drawing” or “I could make a living doing this.” Sugimori: “No, not really.”

When pressed on the issue, Sugimori recalls feeling that the level of art quality in the game industry back in the 80s was incredibly low, which made him feel a certain degree of confidence in his work. Still, it makes you wonder how kids who want to get into the industry for graphic design now feel. How many people get picked up by companies who aren’t graduates of some big name art school?

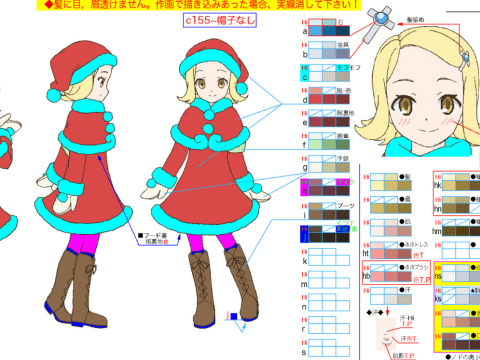

When asked about whether he draws primarily digital or not, Sugimori says he draws things by hand, scans things in and colors it digitally. Also says he really likes the way hand-drawn lines look when zoomed in. “I’m a line fetishist,” he says.

He realized it for the first time in some of Rumiko Takashi’s Urusei Yatsura art books, when he saw some of the blown-up illustrations and thought “these lines are kind of messy, aren’t they?”

This came as something of a revelation. Up until that point he thought manga artists could draw super clean lines as if by magic, but he slowly started to realize that just the opposite was true, and that he really liked imperfect lines, to boot.

“Do you practice or do any studying on your own?” Tomisawa asks. “My day to day work is study enough,” Sugimori responds. If he decides to use a bird motif for a character he makes sure to research bird bone structure and other details so he can get that stuff right. “It’d be embarrassing if I didn’t,” he notes.

“You have to research actual living animals in order to create imaginary ones. You can deform things to a certain degree, but you really have to know your stuff if you want to do a good job,” Sugimori points out. The same goes for human characters, and he consults lots of fashion magazines and other materials for design ideas. He tries his best to maintain consistency with what’s out there in the real world, but he’s not perfect. “My days are spent drawing while doubting whether I’m getting the details right,” he says.

When asked whether he ever has inferiority complex moments when he sees the work from staff members who have illustrious educational backgrounds: “Tons.” Obviously the people trying to work at Game Freak have a huge amount of respect for his work, but he’s nervous that they’re all going to realize what a fraud he is one day. “The only thing I have over them is experience.”

The interview is capped off with a final section where he’s asked about some of his favorite things: Yamato, Gundam, and Robocop.

Re: Yamato, they didn’t have tape recorders back then, but there were records and drama LPs he listened to obsessively, and he drew Yamato stuff constantly. “I could draw the Yamato with my eyes closed.” Still, he’s quick to point out the Yamato boom didn’t last long. They killed off the cast in the second movie, shocking everyone. But then they brought everyone back and kept making more Yamato stuff. Fans didn’t go for it, and the boom was over just as quickly as it started.

“After Yamato was done and buried for good with Yamato Final in 1985, it just kind of seemed so old, like the way the characters were dressed, the blue-faced aliens, everything,” he remembers. Gundam’s style of realism took over after that, but the initial impact of Yamato remains tough to forget.

Sugimori’s also a huge fan of Robocop, even going so far as to buy a jumbo Robocop-shaped bottle of Robocop Bubble Bath from a toy store back when it first came out. No particular reason why. He just really loved that first movie.

Back to games. Among all the game companies out there, Sega is definitely Sugimori’s favorite. Probably because of his first encounter with one of their arcade games: Space Odyssey. “I just liked the look of it. Very colorful.

Other games that made an impression were submarine simulator Periscope and 3D shooting game ZOOM909 (released in the US as Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom). Sega’s games always had this very unique sense of individuality about them, but of course the big one that sealed the deal for Sugimori was Space Harrier. That was the first time he thought “Games are so cool.”

The first Sega console that he really fell in love with was the Mark III, released in the west as the Master System. That marked the start of a console war in Japan between Nintendo and Sega. Nintendo released the Famicom Disk System, which attached to the bottom of the Famicom and allowed players to run disk-based games, so Sega fired back with a series of weird attachments that looked increasingly ridiculous when attached to the Mark III, an endearing weirdness that Sugimori was always fond of. This all culminated in the 16-bit era with the Sega CD hosting a Sega Genesis plugged in on top, which itself had a 32-X plugged into it. “The Baby Turtle Riding on Top of the Mama Turtle,” as Sugimori calls it (It may be worth noting that as of this writing, Sugimori’s twitter account name is @SUPER_32X).

When the topic turns to what he plans to do in his old age, he realizes “well, drawing is my job. Completely. I don’t really want to draw anything for fun. But I still want to play games. Other things may have passed by the wayside, I don’t watch anime anymore, but I still make sure to make time for games.”

The only issue is he’s starting to run out of steam physically as he gets older, he says. But he’s pushed along by the same spirit that led to the creation of Game Freak all those years ago: whatever’s good, bad or weird about a game, as a player he just enjoys all of it regardless. He describes it as the power to get into and obsess over the details. “It’s what allows you to say ‘lately games have all been kind of like X,” or ‘this part is messed up!’ or ‘isn’t it weird that money drops from enemies when you beat them?’ That kind of effort to pick at the details is what leads to new ideas. That gets turned into motivation. And when you ask yourself ‘well, what do I do with that?’ what we ended up with was Game Freak.”

Tomisawa recounts something that Tajiri always said: “You can’t make games from games alone.” Meaning people who only know video games and have no awareness of other art forms are going to be incapable of producing something worthwhile. At the same time, you can’t make games if you don’t know anything about them, either. Which is why Sugimori always tried to go against the grain to some degree. If everyone else was making fantasy RPGs, he’d know not to go in that direction. If it seems like games featuring half-naked girls are the only thing coming out, then he wants to make something that’s just the opposite. That’s just the way he thinks about these things. “Exactly the kind of thought process I’d expect from a creator,” says Tomisawa.

Whew! Cool book! If you’re interested in picking up a copy for yourself, you can still find it at Amazon for around $20 + shipping.

Related Stories:

– Book Review: Masaaki Yuasa Sketchbook

– Your Favorite Anime is Secretly Horrifying: Pokémon

– Man in Pokemon Outfit Jumps White House Fence

– New Pokémon Teased in 2016 Film’s Preview

– Pokemon Cafe Opens in Tokyo