November 3 marks what would be the ninetieth birthday of Osamu Tezuka, the man known both as the God of Manga and the Walt Disney of Japan. During his sixty years on this planet, Tezuka created manga as we now know it, invigorated Japanese animation, and drew more than 150,000 pages of comics. He wrote for children and adults; he introduced complicated themes of timeless storytelling; he waxed philosophically. He could make readers laugh as well as show them the cruelty of the world; he created protagonists both beloved and deeply conflicted. In Japan, everyone knows his name, but in America, one of the countries that purchases the most manga globally, he is still sometimes an obscure name and many of his manga have not been translated.

November 3 marks what would be the ninetieth birthday of Osamu Tezuka, the man known both as the God of Manga and the Walt Disney of Japan. During his sixty years on this planet, Tezuka created manga as we now know it, invigorated Japanese animation, and drew more than 150,000 pages of comics. He wrote for children and adults; he introduced complicated themes of timeless storytelling; he waxed philosophically. He could make readers laugh as well as show them the cruelty of the world; he created protagonists both beloved and deeply conflicted. In Japan, everyone knows his name, but in America, one of the countries that purchases the most manga globally, he is still sometimes an obscure name and many of his manga have not been translated.

For Frederik L. Schodt and Jared Cook, two Americans who worked closely with Tezuka, getting his work to new audiences has become a lifelong mission.

“Fred and I were in the California university system that has an exchange program to Japan,” Cook recalled. “We were both Japanese language majors back in the late 60s, and the junior year abroad in the program sent us over to Tokyo. In our studies and staying in the dorms there, a lot of our fellow Japanese students introduced us to Japanese comics, which were just totally different from anything I had seen before. Fred’s roommate turned him on to Hi no Tori, which had come out a few years before. That one just blew us away – the cinematic way he drew, the storylines and everything. It was as thick as a telephone book.”

Hi no Tori, known as Phoenix in English, is a twelve-volume series Tezuka considered his best work. Before reading it, Cook had had no idea who Tezuka was. Now he and Schodt were determined to meet him. “Fred and I went back to Japan after we graduated and I decided it would be a really good idea to translate Hi no Tori into English. We were just total innocents and had no idea how the business world worked. We went in there and very blatantly said, ‘Hey, we want to translate your stuff and put it into English and introduce it to the world.’ Oddly enough, they took us up on it. We had an almost comical contract: the deal was that Tezuka Pro would give us a complete set of Tezuka’s entire works and a small stipend. It was up to us to produce everything. Tezuka Pro wasn’t really involved in the process except for letting us use their copy machine to copy out the pages as we whited out the little balloons and then wrote in the English in our whited out areas. It was all very rudimentary.”

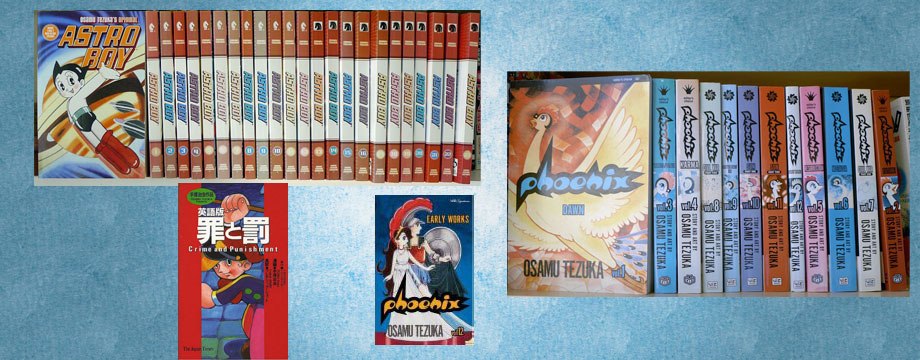

Working with Cook and Schodt were Shinji Sakamoto and Midori Ueda, and they referred to their little group as Dadakai. Together they translated the first five volumes of Phoenix. But the English-speaking world was still not interested, despite the fact that Tezuka’s animated Astro Boy (Mighty Atom in the original) had done well on American TV. Though no one was interested in their translations at the time, Schodt and Cook found themselves working under Tezuka’s wing as English interpreters. They also got to see him through some interesting projects and during some more difficult times.

“His companies had gone bankrupt, all his workers had disbanded, and Tezuka Pro was the resurrection of the original [company] Mushi Productions,” Cook explained. “They were searching around for things to do and ways to become a viable enterprise again. So Fred and I kind of became a conduit for Tezuka to get out in the world and expand his organization. We were interpreters for Tezuka any time he came to the States or did lectures. He traveled frequently and either Fred or I were with him. As a result, I think Tezuka’s name and animation got a lot of recognition. Then I guess RAI Television in Italy was asked by the Vatican to produce an animated series on the Bible. They thought they needed an objective treatment of it, something that wasn’t so influenced by Catholic or Italian doctrine. So they decided, why not go with a Japanese animator?”

Both Cook and Schodt found the idea of Buddhist, agnostic Tezuka working on Bible stories to be amusing. “I in the meantime had become a producer of Japanese television commercials in Los Angeles,” Cook said. “So I was connected with various aspects of the film industry. Since this was going to be distributed worldwide, they were thinking they’d produce it in English and then dub it into other languages. So I hired voice actors and put together the crew and got to direct some of the voice work for the animation and then put together the people who put together the codes for the mouths. Pull all that together and ship it off to Japan so they could animate the series. As it turned out, they got something I think a little different from what they were anticipating. They wanted an objective viewpoint, but what they got was Tezuka’s own personal stylized take on the Bible, which featured a little fox that was very naughty and always running around and getting into trouble. It would almost steal every single scene. It was a very enjoyable piece, but I don’t think it conveyed the religious message the Vatican anticipated. I’m not sure if it ever even aired. It might have gotten pulled before it was ever completed.”

(In fact, Tezuka’s Bible stories have aired selectively in different countries, including in America on the Catholic channel EWTN, though it happened years later. And the fox’s naughty antics did not always survive censorship.)

Tezuka overcame any setbacks and continued to work on his manga. “Tezuka was very much loved by the Japanese people,” Cook said. “He just had incredible enthusiasm and energy and was a bonafide genius. He could not turn his mind off. He was a creative guy who never stopped creating. He’d only sleep three to four hours a night and the rest of the time he was working. We’d be here in the States, staying at a hotel, and there would be an entourage of editors who would follow him. One by one they’d be pounding on his hotel door to make sure he was still awake and still working so in the morning they could grab the latest drafts and hop on the plane to take them back to Japan to be published the next day. He had that many assignments and that much work backlogged. A lot of people say he was kind of gruff and could be temperamental. But working that hard, putting so much effort into it, and [being] so obsessed with the creative process and all the ideas coming up in his head, a lot of times he didn’t have time for the social graces. He was really focused on getting the work done.”

Eventually, American publishers did start to pay attention to Tezuka. Phoenix, his masterwork, was published by VIZ in the early 2000s. “They were all set to go about and retranslate it when Fred got wind of it,” Cook recalled. “We called them and said, ‘Wait, wait, wait! It’s already been done!’ We dusted it off from the Tezuka archives and got it published.” After the first five translations by Dadakai, Cook and Schodt translated the next seven volumes for publication.

Besides VIZ, Digital Manga Publishing, Dark Horse and Vertical have all published Tezuka titles. But many Tezuka titles remain untranslated, and some, like Phoenix, have already gone out of print.

“It’s always been a challenge [to get him in English],” said Schodt, who is the author of the first English-language book on manga, Manga! Manga!, which Tezuka wrote the introduction to. Schodt is also the author of The Astro Boys Essays. “People have only scratched the surface of what he created if they’re reading in English. Companies like Vertical, Dark Horse, and DMP, they would be great companies to encourage to publish more. Tezuka Productions always has projects in the works to keep his name in people’s minds.”

“It’s always been a challenge [to get him in English],” said Schodt, who is the author of the first English-language book on manga, Manga! Manga!, which Tezuka wrote the introduction to. Schodt is also the author of The Astro Boys Essays. “People have only scratched the surface of what he created if they’re reading in English. Companies like Vertical, Dark Horse, and DMP, they would be great companies to encourage to publish more. Tezuka Productions always has projects in the works to keep his name in people’s minds.”

Natsu Onoda Power, a Georgetown professor and author of God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post World War II Manga, has also made it her mission to spread the name of Tezuka. Growing up in Japan in the 1980s, both she and her brother wanted to be cartoonists and would create their own manga. “When I was twelve I went to Tezuka Productions,” she said, recalling how Tezuka was seen as a godlike figure then. “They had a visitor day when fans could come in and observe how things are made. I had secretly brought my work and Mr. Tezuka happened to be there. I asked, ‘Can you look at my work? Can I be your assistant?’ He said I should finish middle school first. It was a seminal experience for me. He said something like, ‘Come back in three years, and if you have made progress and still want to be part of this, we’ll speak about it then.’ And then he died two and a half years later.”

Onoda Power was not able to work for him, but so much of his work inspires her. “I started reading not only his manga, but his essays and such. So his words had a really profound influence on me as a storyteller in another medium. I take it as my mission to promote his work whenever I get a chance. I’ve done a play that’s based kind of on Astro Boy but is about Astro Boy the series. It’s half biography of Tezuka and half making of Astro Boy. I’ve done an adaptation of three short works of Tezuka, three works that are not translated. I was recently commissioned to write a children’s play and I proposed an adaptation of his work on tuberculosis. It hasn’t been translated. It’s one of the earlier ones. It was interesting because I proposed it to the company that wanted something new, and they said they’d be thrilled with an adaptation of a manga because that would be appealing to their audience. I explained the premise of their book. [The characters] accidentally shrink themselves and enter a human body and meet tuberculosis viruses and they develop a relationship with them. They’re faced with a moral dilemma whether to fight the tuberculosis or not because they’re friends, but they learn they’re harming the body. I can’t think of any single figure that has been so profoundly influential on artists, not just in manga, in twentieth century Japan.”

But it’s not just people who knew Tezuka who feel a need to talk about his work. “I believe Tezuka is not only the most significant figure in the postwar manga era, but also a major bridge between the prewar and postwar era, linking the early years of manga with the postwar revival,” said British writer Helen McCarthy, author of The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga. “Frederik L. Schodt’s magnificent work aside, there was very little material on Tezuka in English, and nothing that gave a detailed overview of the range and depth of his career. So I thought, since nobody else had done it, I should try. Luckily I already had contacts at Tezuka Production through an earlier project, so I was able to approach them.”

Ada Palmer, a Chicago University professor, SF/F author (and, it turns out, big fan of Otaku USA), founded the site TezukainEnglish.com. “I became enthralled by Tezuka’s work when the first of the two early VIZ paperbacks of Black Jack came out — I remember I read it while walking back to my dorm from the comics shop and liked it so much that I never went into the dorm and turned around on the doorstep to go back and buy volume 2,” she said. (Black Jack is now being published by Vertical.) “And then I learned about how many other works he had, and how important he was to manga/anime history. At the time there was no information online about Tezuka in English at all, so I created a small website just so there would be something that people could find, with information about his historical significance, his different works. And as I read more of his works and saw how he uses the Star System to connect them together, I wanted to post essays about how his works connected together, to help people who had read only one discover how much richer they all become if you read more. That’s a lot of what I talk about in my published essays in Mangatopia and Manga and Philosophy. Pretty soon I was contacted by Tezuka Productions, who wanted to know if I would work with them on English language publicity, so we had a meeting, and we linked my site to the Japanese site, and it became a sort of semi-official gateway, though still fan-run. I expanded it over time, but as my own writing and publishing started taking more of my time, I eventually handed it over to Greg Baker a fellow fan who’d volunteered some time earlier to make it a new better layout etc., and he’s been maintaining it since, while I’ve been doing more scholarly work on Tezuka. But I’m still in contact with Tezuka Pro and help spread the word whenever there’s a new Tezuka release.”

So where does Tezuka stand with publishers now?

So where does Tezuka stand with publishers now?

Chris Warner, Senior Editor at Dark Horse Books, talked about why his company decided to take on some Tezuka titles. “Dark Horse, from the very beginning, had desires to publish the best comics from all over the world. Astro (or “Mighty Atom”) is one of the true iconic comics characters, Tezuka is carved on the Mount Rushmore of comics creators, and Astro Boy is one of the jewels in the crown of manga. More on a personal note, the Old Guard at Dark Horse had all been fans of the Astro Boy cartoons when we were kids, so we felt we absolutely had to go after it. Luckily, we acquired the rights and have been publishing Astro Boy ever since. It was a great honor and my pleasure to oversee the English-language edition, translated by the great Fred Schodt. Astro Boy is one of my editorial career highlights. We have published other Tezuka titles: Metropolis, Lost World, and Next World.”

Asked if Dark Horse might license more Tezuka titles, he said, “I think most of the other more known Tezuka licenses are tied up with other publishers; but maybe down the line, who knows?”

Ioannis Mentzas, Editorial Director of Vertical, also answered why his company chose to license Tezuka classics, including Buddha, Princess Knight, and Ayako. “We felt like the Tezuka of the 70s and on, who had re-invented himself for a maturing (i.e. older) demographic, would have the best chance here packaged as classic graphic novels.” As to whether there were plans to license more Tezuka titles, he said, “Not at the moment.”

VIZ declined an interview.

Digital Manga Publishing, which has backed Tezuka through Kickstarter, sounded eager for more Tezuka. “We wanted to reach out to more people outside of our usual fanbase or boundary,” DMP President Hikaru Sasahara said about the Kickstarter campaigns. Some of the titles they’ve brought out in English include Swallowing the Earth, Barbara, and Unico. “Yes, we are proposing to Tezuka Productions that we would like to publish ALL of Tezuka titles in the future.”

Digital Manga Publishing, which has backed Tezuka through Kickstarter, sounded eager for more Tezuka. “We wanted to reach out to more people outside of our usual fanbase or boundary,” DMP President Hikaru Sasahara said about the Kickstarter campaigns. Some of the titles they’ve brought out in English include Swallowing the Earth, Barbara, and Unico. “Yes, we are proposing to Tezuka Productions that we would like to publish ALL of Tezuka titles in the future.”

In publishing, as with any business, an interest in a specific author (especially when it comes to buying their books) is the best way to help get you other books by the same author. “Buy all the existing titles, post about how great they are on social media, and advocate widely for the titles they’d like to see next,” McCarthy said as her advice to get more Tezuka licensed.

“Right now most new Tezuka is being released by DMP through Kickstarters, and they’re putting new things out at a good clip, so subscribing to their Kickstarter updates and pledging to support is ideal,” Palmer said as her advice. “But unfortunately they’re mainly doing very limited releases without really shipping to comics shops or libraries, so things are coming out and then disappearing. So one thing that I think could make a huge difference would be if people go in person to your local comics shops and ask them to order you whatever Tezuka title you’re interested in trying. When small comics printers get orders from shops, that means a lot more to them than online orders, both because of details of where the money goes, but also because presence in stores reflects in expanded sales as people see things on shelves. If comics shops can be convinced to stock and sell Tezuka, then publishers will be more likely to try doing more widespread versions of the releases they’re undertaking.”

Since Tezuka wrote more than 700 manga series during his lifetime, he is often described as prolific and a genius. The people who love his work want to see more of it. And the people who knew him say he was unlike anyone else.

“The more I look back on the time I spent with him, I realize I didn’t appreciate that enough,” Cook said, reflecting on his days with Tezuka. “The themes that he deals with are timeless. His experience through wartime and his take on what that does to culture and religion and reincarnation. . . the scope of the stuff he deals with is just amazing.”

_____

Danica Davidson, along with Japanese mangaka Rena Saiya, is the author of Manga Art for Intermediates. In addition to showing how to draw manga character types in detail, the book describes how professional Japanese manga creators work, including common techniques and what drawing utensils they use.