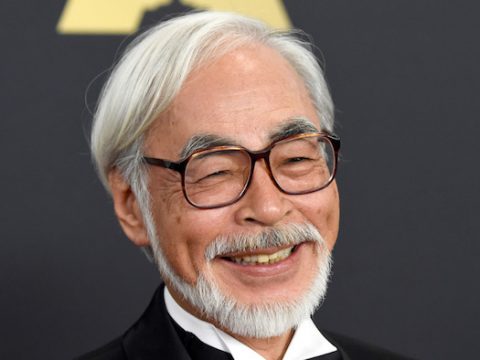

A few weeks ago, Berkeley’s Center for Japanese studies awarded Hayao Miyazaki with the Berkeley Japan prize for, among other things, “”[furthering] our understanding of Japan and its contribution to global culture.” “Rare opportunity” sounds really cliché, but honestly, that’s what we had – how often is one of the greatest Japanese animator/directors who ever lived just chilling across the bay? Tickets for his evening of conversation with Roland Kelts (author of Japanamerica and lecturer at Tokyo University) sold out quickly, but I managed to snap one up.

I attempted to at least sneak a shot of the chairs Kelts, Miyazaki, and the interpreter would be sitting in, but the ushers were zealous in their pursuit of zero photography. They actually had us turn off our cell phones before we even entered the auditorium.

The mezzanine at Zellerbach Hall is pretty well overhead, so it wasn’t always easy for me to make out his exact expression, but Miyazaki was pretty much exactly what you might expect – like somebody’s friendly grandpa. Many of his answers were preceded by a deep, bear growl thinking noise that set the largely student—but also just straight-up Studio Ghibli fan—audience giggling a bit.

First, Kelts asked a question regarding the virtual worlds of today’s young people and whether that could cause them to lose their imaginations, which Miyazaki pretty much shrugged off, “Old people always comment that nowadays things aren’t that good. Yes, there are many virtual aspects in the world today, but when I was a child, probably compared to 100 years before that, there were also more virtual things… so, even before the age of videogames and television when perhaps movies were the virtual world that people saw, we still had problems then.”

He’s more concerned about “…whether there’s an end point to civilization, if we’re coming to some sort of end of the world type era now,” although he didn’t specify what he thought might precipitate such an event. (Fans of his work might guess anything that negatively affects the environment?)

When prompted to discuss this apocalyptic sub-text a bit further, he said, “It would be wonderful if I could see the end of civilization during my lifetime, but it doesn’t seem like it’s going to happen. And so, that’s why I use my imagination to think what it might be.” That said, he did clarify that particularly in Ponyo (coming to U.S. theaters this month with a great dub by Disney), “…this tsunami doesn’t destroy the town or the people there, it’s kind of a magical, a cleansing tsunami for the town and the people who live in there, and it’s that kind of hope that I see in the power of nature.”

Then the conversation turned to perhaps a connection between nature, apocalypse, and nostalgia. Miyazaki came at the implication from a sideways angle, discussing instead his hometown where sometimes the river floods and “…the old people come out of their houses on the alleyway and get very excited.” He seemed impressed with the human spirit during these seasonal trials, noting that, “They think they have to save the person who’s in trouble and they become better people.” When his wife and he rebuilt their house, they decided not to raise it up: “[We] are willing to get flooded together with the people around us. We think it’s better that way.” In fact, his entire outlook on the flooding is pretty positive, since, “We manage the local forest and after the flood, even though there’s a lot of junk that’s flooded into the forest, the plants and trees there seem healthier after being flooded and so water brings good things as well. So I don’t think we can equate some natural disaster with something really bad happening as a calamity, but as something that we live together with.” He actually also confessed the truth about his evil side, “…when I go to the top of one of the high rises in Tokyo and look at the scenery below, I think that it would be better if the sea came a little closer and there were less buildings down below.”

This led Kelts to ask about true evil in Miyazaki’s films, since the villains often seem to be “more troubled…than evil.” Miyazaki replied in a whimsical fashion that disappointed some, “To have a film where there is an evil figure and the good person fights against the evil figure and everything becomes a happy ending – that’s one way to make a film, but that means you have to draw, as an animator, the evil figure, and it’s not very pleasant to draw the evil figure, so I decided against having evil figures in my films.” It’s as simple as that!

From there, they ended up discussing Miyazaki’s use of people he knows (and staff members!) as models for some characters in his films. For instance, the chief animator in Ponyo, Katsuya Kondo, is the basis for Fujimoto (Ponyo’s father). He also mentioned a background artist, Noburo Yoshida, who may be “having a hard time with re-entry into society” after being encouraged to “explode in [his] childishness” in order to attain “…that kind of really childish naïve vividness…”

They ended up back on the subject of Ponyo (which annoyed some attendees because they hadn’t attended the premiere the previous evening and lacked context) – did you know she started out as a tin toy frog instead of a goldfish? But actually the main subject of this portion of the talk became why Miyazaki makes such an “imaginative leap” rather than making designs “rooted in biological models” where “…Mickey is a mouse, Bugs is a bunny, Donald is a duck.”

To me, this seemed like sort of a ridiculous question to ask a man whose imagination is the whole purpose he is praised and loved around the world, but luckily the answer he gave was sort of oblique:

“When we draw animals, we have to draw their eyes, and in order to simplify things some animators draw eyes that we can really understand and look into, but I think nature is beyond our understanding – it goes beyond our own psychology, so when we were making Totoro I told my animators to make sure we didn’t know where he was looking. He’d just have his eyes looking down. And with the ohmu in Nausicaä, we don’t know where their eyes are looking at all because they have them all over; they have many eyes, and it’s hard to tell what they’re thinking or what they’re looking at. So I explained to my staff that we have to make Totoro so we can’t figure out whether he’s really smart or really stupid – he might be thinking very deep thoughts or he might be thinking of nothing.”

The most interesting thing he had to say about Spirited Away was about how Chihiro enters into the fantasy world (after the transformation of her parents into pigs after gorging themselves on Chinese food, which he said he meant as “…a rather normal type of situation” and not satire):

“When we’re making a fantasy, the simplest way to show that it’s a fantasy realm is to have the characters go through a tunnel or maybe open up a door in a shelf and there’s another world behind it. In Spirited Away I was trying to find a better entry point into the fantasy, so I had her looking for entry points, but of course then the scene got very long and we couldn’t really start the story of her being in the fantasy world, so I threw away all that and used the tunnel entrance after all.”

When Kelts replied, “It works,” Miyazaki added, “Yeah, I just thought I was sort of cheating myself by making it such a simple entry point, but what can you do?”

In response to the mention of what a “strong, independent, curious, ambitious young female” protagonist Chihiro is, he revealed that Studio Ghibli is currently training new animators:

“From this April we have 22 new employees who were hired as animators, and of those four were men; now we’re in the process of trying to hire ten more animators and we’ve been going through the hiring process (there are tests that they have to take) and of the 22 that are remaining, we still have to cut it down to about half, but there’s only one man that remains among this pool of candidates. So because there are so many strong women now I think I might have to start making films about men.”

I wish Kelts would have asked if Miyazaki had ever considered adapting a manga instead of asking why he didn’t (like the majority of anime directors do). Miyazaki’s answer, however, was pretty interesting:

“I think we can just enjoy manga by reading manga as they are. Of course, if you animate it, you can perhaps add some features to the manga, but I think if you can avoid making manga into animations, it’s better. Manga and film have very different concepts of time and space, and unless you are very aware of that then the ultimate product can become very boring and uninteresting. You have to know that the sense of time in terms of expanding time and condensing time, stretching time and space as well, is very different in the two media.”

All images © Studio Ghibli / Disney