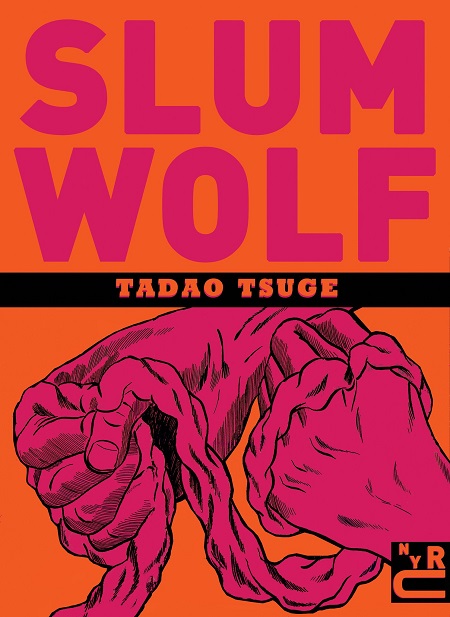

Born into a poor family in 1941, Tadao Tsuge grew up in the chaos and poverty of immediate postwar Japan: a rundown Tokyo of open sewers and ruined buildings, populated by thugs, prostitutes, and occupying American GIs. In the late 1960s and 1970s, these memories formed the core of the stories in Slum Wolf (and its accompanying collection Trash Market from Drawn & Quarterly), published in underground manga magazines like Garo and Yagyo (“Night Wandering”), islands of social realism and experimental artistic techniques in a commercialized manga world. While mainstream manga became increasingly glossy, polished, and middle class, these outlets provided a place for art like Tsuge’s—rough and cartoony—and stories of the poor, forgotten, and dispossessed.

Born into a poor family in 1941, Tadao Tsuge grew up in the chaos and poverty of immediate postwar Japan: a rundown Tokyo of open sewers and ruined buildings, populated by thugs, prostitutes, and occupying American GIs. In the late 1960s and 1970s, these memories formed the core of the stories in Slum Wolf (and its accompanying collection Trash Market from Drawn & Quarterly), published in underground manga magazines like Garo and Yagyo (“Night Wandering”), islands of social realism and experimental artistic techniques in a commercialized manga world. While mainstream manga became increasingly glossy, polished, and middle class, these outlets provided a place for art like Tsuge’s—rough and cartoony—and stories of the poor, forgotten, and dispossessed.

Of course, as translator Ryan Holmberg points out in his accompanying essay, there is also a stereotype in Japanese pop culture of romantic, maudlin depictions of the dispossessed—the noble prostitute, the lone manly wanderer, the last honorable yakuza, etc.—and a counter-stereotype in underground comics of shallowly nihilistic Yoshihiro Tatsumi-style “social realism” where everyone sucks. While Tsuge has moments of nostalgia and romance, his greatest successes come when he creates understated stories where the characters are deeply flawed but still sympathetic and believable, and the only climax or catharsis may be someone throwing a beer bottle in a dark street to hear the crash break the stillness.

A recurring theme is violent thugs headed for self-destruction (like the fight-picking protagonist of “Punk”) and scarred WWII vets (like the weary businessman in “The Flight of Ryokichi Aogishi”), or characters who are both at once, like ex-kamikaze Keisei Sabu in “Sentimental Melody.” “Without receiving a dose of pain once in a while, it was hard to remember the point of staying alive…” muses legendary criminal Sabu in “Legend of the Wolf,” a worn-out man at the end of his life, yet still a shining hero to the story’s protagonist. An even more bizarre father-figure shows up in “Bum Mutt,” the only openly surrealist story. But while Tsuge’s subject matter is generally realistic (the thugs-meet-hippies scene in “Punk” feels real, and funny), his darkness-smeared artwork and strange story rhythm places his work somewhere outside the real world; if “Sounds” had been written by Yoshihiro Tatsumi, it would be just another misogynistic conte cruel, but in Tsuge’s hands this fragmentary tale of a wandering drunk haunted by guilt has the chill of a cryptic ghost story.

This sense of unworldliness reaches its peak in “Vagabond Plain,” a longer (yet, somehow appropriately, unfinished) story set in a ramshackle community on a grassy riverbank, where people with nowhere else to go have built a settlement of shacks destined to be destroyed when the first rainfall floods the river and wipes it away. (“Around 1949, 1950, the country was practically inundated with such people, wandering about with no particular aim…”) In contrast to the sadness of the other stories, “Vagabond Plain” has a weird sense of anarchic abandon, almost hope, like the liberated inhabitants of the perpetually burning city in Samuel Delany’s novel Dhalgren, finding a new mode of life in the ruins. Characters seem to reappear between this and the other stories, though their appearances and details change, while the author’s friendly-looking alter ego wanders through the margins, asking questions. An illustrated essay by Tsuge goes into his inspirations for his work, providing fascinating context to these tales of another world, a world of memory and the past. Recommended.

Publisher: New York Review Comics

Story and Art: Tadao Tsuge

Rating: Unrated/18+

![Yokohama Station SF [Manga Review] Yokohama Station SF [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Yokohama-Station-SF-v2-crop2-480x360.jpg)

![Manner of Death [Review] Manner of Death [Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/manner-of-death-v2-crop-480x360.jpg)

![Origin [Review] Origin [Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/origin-10-crop-480x360.jpg)

![Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review] Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RoV_Vol2_Front_CoverArt_V1-480x360.jpg)

![SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review] SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/16-9-SSSS.Dynazenon_Key_Visual_3.5-480x360.jpg)