It really is about who you know. Through an amazing chain of unlikely events, I got to see the live-action Space Battleship Yamato movie, fully subtitled in English, three and half weeks before my plane ticket says I’m flying to Japan for the December 1 premiere. This was courtesy of a connection to the American Film Market, one of those exclusive L.A. festivals open only to industry people and those who can figure out how to weasel in. Count me as one of the latter. (Though it didn’t hurt that I could hold up my work for starblazers.com as street cred.)

It really is about who you know. Through an amazing chain of unlikely events, I got to see the live-action Space Battleship Yamato movie, fully subtitled in English, three and half weeks before my plane ticket says I’m flying to Japan for the December 1 premiere. This was courtesy of a connection to the American Film Market, one of those exclusive L.A. festivals open only to industry people and those who can figure out how to weasel in. Count me as one of the latter. (Though it didn’t hurt that I could hold up my work for starblazers.com as street cred.)

Open on extreme closeup of an eyeball. Breathing and nondescript sound effects. Flashes of distant light reflect on the retina. Two seconds later our camera is yanked violently out of a Black Tiger’s cockpit as pilot Yuki Mori dives into a torrent of laser fire in the shadow of Mars. A procession of dull grey Earth ships is fighting a last stand against an absolutely overwhelming enemy. Far from home, outmatched in every way, their fate is decided within five minutes of screentime.

From the moment the film was announced in the summer of ’09, the theme of every conversation about it was “compromise.” How much of the TV series could be cut away and how far could you stray from the original before losing the core? But then, Yamato has been a compromise from its very beginnings when a 39-episode plot was chopped down to 26 and constant production battles filled every episode with animation errors.

Then there were all the compromises inherent in its conversion to Star Blazers, which were enough to ignite a generation of self-selected anime purists. The compromises continued even decades later when the franchise entered legacy territory and its creators pulled it in directions it was never meant to go. The bottom line is that a “pure” Yamato is only a fantasy; it’s the part you fill in with your own mind.

That is the proper mindset in which to view Director Takashi Yamazaki’s Yamato. Space-warping from anime to live action can be either traumatic or revelatory, depending on your resistance to compromise. Being a 30-year consumer of all things Yamato could have made me a candidate for trauma, but I managed to escape that fate. When the movie’s teaser trailer emerged on January 1 it had me hooked in under 30 seconds, and the two subsequent trailers that followed in the spring and summer proved to me that we didn’t need this to be 100% accurate. We just need it to remind us what it felt like to see Yamato for the first time.

It’s difficult to describe the plot without unleashing a chain of spoilers, since the film rockets by without a single wasted frame. All I can confirm is that everyone who speculated it might fuse the Iscandar story together with the Comet Empire was absolutely right. I was initially skeptical of this, since I couldn’t imagine compressing that much material into a single feature. But Yamazaki and his crew apparently began their work with an “all the marbles” mentality, and that’s what they’ve delivered.

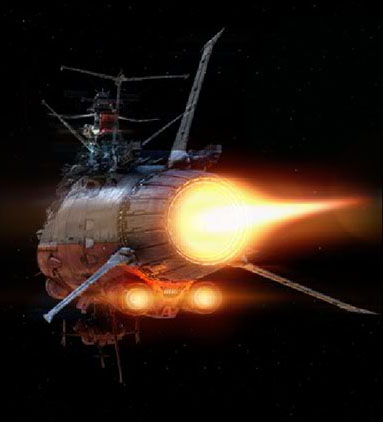

On the other hand, some of the details are fair game. The mecha design starts from the anime but never allows itself to be limited by it. Yamato, the Black Tiger, and the Cosmo Zero have the same basic silhouettes they always did, but each has something more to offer in the medium of CG. It’s rather unfortunate that Bandai chose not to sign on as a licensor of the film, since I’d love to see all three rendered as real-world objects. Instead, it looks very doubtful (at this point) that we’ll get toys or models of any kind.

The Gamilas ships, as evidenced in the trailers, bear no resemblance at all to their anime counterparts; they’re far more alien and amorphous, a creative choice founded upon alterations to the race itself and also a disconnect with the original production design owing to the non-involvement of Leiji Matsumoto. That, in fact, encapsulates the biggest break from the anime; the ship interiors, while more realistically proportioned, sport not a single “Leiji meter” or even a nod toward his handmade World War II aesthetic.

In fact, the Yamato itself isn’t as prominent in the film as you might expect, I grudgingly admit that it’s probably for the best. As much as I longed for a CG redo of that famous flyby shot from the anime, it wouldn’t have served much purpose here. Adjustments like that resulted in the departure of the film’s initial director, Shinji Higuchi, who made Lorelei, Witch of the Pacific (2005). Word on the street has it that when the script evolved from an SF war story to a character drama, he stepped aside for Takashi Yamazaki, who had just swept the Japanese Academy Awards with his 1950s ensemble film, Always: Sunset on Third Street (2005). Though the tone of Yamato is very different from Always, the ease with which Yamazaki weaves character drama in both is undeniable.

That said, a consistent criticism that has been leveled against his previous films—not without merit—is that they draw heavily on very obvious references. Juvenile (2000) smacked strongly of both E.T. and Independence Day. Returner (2002) wore its Terminator and Matrix badges without shame. Both of the Always films and the time-travel fantasy Ballad (2009) started out as manga and anime respectively. Understandably, a track record like this casts doubt on Yamazaki’s ability to create something wholly original. Yamato continues the trend with production design and plot points that speak loudly of his respect for Battlestar Galactica.

Yamazaki balanced the scales in his previous works by finding an original way to twist his references, blending the familiar with the surprising; exactly what he does here. Higuchi might have given more camera time to the mecha (which he certainly did in Lorelei), but there’s no evidence that he shares Yamazaki’s proven ability to step into someone else’s playground and appealingly make it his own.

Packed to the gills as the film is with new and unexpected elements, there’s one major exception which should make for an encouraging closing note: the music. You hear the original Yamato theme within the first minute and it comes up again several times throughout the movie, along with the “Infinity of Space” theme and possibly one or two others. It isn’t a straight lift from the anime BGM, since the soundtrack is entirely the work of Yamazaki’s regular composer Naoto Sato, but the classic sound is expertly woven into the lifeblood of the new score and reminds you where you are at all the right moments. It’s just as important a character as Kodai or Yuki, and its absence would have been glaring. Regardless of how you eventually judge the film’s authenticity, you’ll be enjoying the soundtrack for years to come as a love letter to the one part of Yamato that never had to be compromised.

And now the countdown to December 1 begins. It’s only been a few hours, but I’m already looking forward to my next viewing.

Tim Eldred

November 6, 2010

Visit www.starblazers.com for much more Yamato, new and old.

Visit the movie’s official website here: https://yamato-movie.net/

© 2010 「SPACE BATTLESHIP ヤマト」 製作委員会