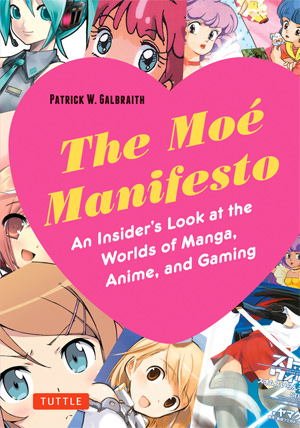

Otaku expert Patrick Galbraith is out with a new book, The Moe Manifesto, which explores the moe phenomenon with interviews from various moe fans, detractors and experts. We continue our interview with Galbraith as he discusses a famous otaku feud and Tokyo’s recent prohibition on “unhealthy” manga.

OUSA: Going to back to how a lot of these interviewees often don’t get along, one of the interesting rivalries that you cover in the book is Eiji Otsuka versus Akio Nakamori. Can you explain the background behind that?

Galbraith: Yeah, this is something that comes across strongly in my interview with Otsuka, but in his own books and essays, he has been on Akio Nakamori’s case for a long time. Basically, Nakamori is credited with being the first to use the word “otaku” to refer to an imagined grouping of fans in Japan. In his first article, Nakamori uses the word to make fun of socially awkward or uncool fans, people who need to “get a life,” so, like people lining up the night before an animated film opens in theaters. Nakamori’s articles, what he called his “research” of otaku, were published in Manga Burikko in 1983 – under Eiji Otsuka’s watch as editor of the magazine.

The story goes that Otsuka was against it from the beginning, because he felt that Nakamori was just picking on people to build himself up. In our interview, Otsuka argues that Nakamori wanted to be a cool kid. He says that Nakamori was kind of a trend-conscious, outwardly oriented, recognition-seeking guy, and for that reason he belittled certain kinds of fans that were not as “cool” as him. For Otsuka, Nakamori represents the shinjinrui, or the “new breed,” who were basically Japan’s version of the hipster in the 1980s. Otaku were the anti-hipsters, in that they didn’t really care about being cool and were all too serious about what they were in to. So, for example, there was no irony in loving anime for these guys.

Akio Nakamori

Nakamori’s articles are at times pretty venomous. Some say that he was just trying to be funny, and maybe that’s true, but in the process he calls people leeches, slugs, queers – all sorts of names. Nakamori is describing people this way, and all of this gets wrapped up in his newly imagined category of “otaku,” which was a pejorative, insult or put-down.

Nakamori makes fun of just about everyone in his first article, but it turns out that there is a group of people that offend him more than any other, and they are the ones who attend conventions like the Comic Market and produce fanzines about their favorite characters. He thinks these guys are just weird, and he identifies them as lolicon, which meant at the time people who are attracted to fictional girl characters from manga and anime. In his second article, Nakamori says that the problem with “otaku” is that they’re in love with fictional characters, so they can’t be normal. Let me rephrase – he says that they can’t love like normal people. They are “warped.” And in this context he calls them “queers.” Sort of like Brony bashing, right?

In his third article, Nakamori goes to a cafe called Free Space in Shinjuku. This time, he has his girlfriend with him. Together, they come across these really deep otaku who are looking at anime magazines and posters and talking about their favorites series. This might seem to us like a bunch of guys sharing their love of anime, but to Nakamori’s eyes this is a hellish scene of utter depravity. These guys are just so gross that he tells the reader that he couldn’t suppress a shudder. He paints this scene where his girlfriend looks at these guys and shrieks in horror.

So there you have it. Nakamori – the normal, cool dude – looking at otaku – the abnormal, uncool dudes. Nakamori has a girlfriend – a real one, he reminds us – while these guys just have their warped desire for fictional girl characters.

Eiji Otsuka

For Nakamori, this orientation toward fiction is kind of the baseline by which he judges these guys as abnormal and gross. So, in a way, you could say the “problem” with the people called “otaku” in Japan was from the very beginning about desire for fictional characters. To put it another way, Nakamori, who grouped uncool fans together as “otaku,” had a problem with what we now call moe.

Otsuka didn’t like the way Nakamori picked on people, especially since Manga Burikko was catering to so-called manga maniacs attracted to fictional girl characters. So, you know, it was like Nakamori was spitting in the face of the readers. Worse than that, though, are the consequences of labeling some people as abnormal or weird. Once you draw this line and label guys on the other side as deviants or perverts, others will follow you. Which is exactly what happened when the mass media turned to “otaku bashing” in the 1990s.

So, as I understand it, Otsuka’s major problem with Nakamori is that this guy, in dealing with his own insecurities and desire to be cool, ended up othered this group and setting them up to be scapegoats and media whipping boys for years to come. It’s about discrimination, right? Or at least that’s how Otsuka sees it.

Nakamori, of course, has a different story. He was just a young guy writing a column in a minor manga magazine, and his editor canceled his column without any warning. Not even a phone call, Nakamori says. And then he hung Nakamori out to dry as public enemy number one among Japanese “otaku.” So, Nakamori sort of sees himself as a victim in all this.

It’s kind of wild that Nakamori used “otaku” for the first time in this very non-mainstream magazine, but it got picked up and entered the lexicon. And he was, what, 23?

The header for Nakamori’s first column.

He was born in 1960, so, yeah, about 23. He was a very young man, and not particularly famous at the time. You have to admit, he did make a name for himself. Some people argue that why people are so mad at him, and why the word otaku stuck, is that he was on to something. You know, there was something there that he was responding to, and he just put a label on it. In the case of attraction to fictional girl characters, so-called lolicon, the stuff that really made Nakamori’s skin crawl, we still see articles relating this to “otaku,” Articles still pop up in the media all the time. The BBC did one as recently as 2013, you know, saying something like, “There are these men in Japan called otaku who are attracted to manga, anime and game characters instead of real women and that’s why Japan’s population is falling.” It sounds like something Nakamori could’ve written in 1983. Something is making people anxious, and they point the finger at this imagined category of “otaku.”

I think the backlash against moe reveals something, too.. In a way, it really resonates with that original othering of otaku culture. “You know, we’re all into anime now, but there’s still some weirdos. I mean those guys over there who are into moe anime. What’s up with them?” You know what I mean? That’s basically what Nakamori did. Today, otaku as a label can be claimed with pride, and some even think of otaku culture as cool somehow, but then you have people or objects of affection or fan practices that make people uncomfortable. Uncool stuff at the heart of Cool Japan, supposedly abnormal stuff that disrupts the normalization of “otaku.” Then you have a new label – moe otaku – which serves the same purpose as what Nakamori originally meant when he said “otaku.” We are still discriminating against people we perceive to be different.

A few months ago the Tokyo government enforced a new rule for the first time, deeming Imouto Paradise 2 unhealthy. Does Imouto Paradise 2 fall into the “moe” category?

Well, it’s an adult manga based on an erotic visual novel, so I’d say that it’s wank material. It’s not exactly mainstream manga, you know? Where it might overlap with the moe phenomenon, though, is that you have really cute characters and people who are into those characters.

Here I draw on Toru Honda, a sort of moe guru that I interviewed for the book. Anyway, Honda says, “Hey, I masturbate to adult manga and anime, and that’s one thing, but I am also married to this character and I love her, and that’s another thing.” Honda’s wife is a character from an erotic visual novel, but his relationship with that character is way beyond just playing a game and wanking to a character image. I can see Honda’s “abnormal” relationship with a fictional character offending some people. Go Ito, who I also interview in the book, calls this “moe phobia,” which is people afraid of and reacting violently to what they don’t understand.

But I don’t think that the Tokyo government was really interested in any possible moe aspects of Imouto Paradise 2. Consider the content – brother-sister sex. OK, that’s raunchy, but porn often is. As I understand it, the Tokyo government felt that this manga glorified incestuous relations, which is why they deemed it “unhealthy.” They want stuff like this to be zoned out of places where kids can see or buy it, because, after all, the ordinance is about the healthy development of young people. They only care about guys like Honda to the extent that they see them as examples of someone who has been “warped” – I hear Nakamori, again – consumption of “unhealthy” media consumption. They don’t want kids to turn out like him. Kind of like how in the US some people are worried about exposure to homosexuality turning their kids gay, you know?

You can probably tell that I’m not a fan of this type of ordinance. I worry that once we start policing media content because it seems “unhealthy” then we end up sliding into a type of conservatism. “Oh, no! Don’t look at that! You might get the wrong idea!” The wrong idea? So you mean that there is a right idea and I should have that? I see. And then from there it’s a short hop to censorship and thought policing. “This media gives the wrong idea. Destroy it. This person has the wrong ideas. Arrest him.”

Don’t get me wrong – I’m not saying that the content of Imouto Paradise 2 is awesome. But it does worry me that the government is taking more of an interest in making sure that we grow up healthy and don’t encounter media that might give us the wrong ideas. I don’t think that it’s surprising that they took on Imouto Paradise, because it’s got a decent fan following, has an emphasis on incest, which is one act specifically mentioned in the ordinance, and the characters are marked by a kind of cuteness that’s worrisome for a lot of people, because cuteness often bleeds into youthfulness.

Galbraith

I think that we are going to see a lot more of these high-profile actions against objectionable content in the lead-up to the Olympics, which are to be held in Tokyo in 2020. Especially vulnerable are manga, anime and games, which are sort of the core contents of “Cool Japan” and are very import to the image campaign and international PR. The government is taking more of an interest in policing manga, anime and games because of their strategic importance. Imouto Paradise 2 is an easy target. Let’s see what is next.

I don’t want to belabor the point, but just one more thing on the conservatism implicit in policing purely fictional content to make sure that people don’t get the wrong idea. I think that it’s good to be challenged by things, and I’m not ready to shut down the discussion just because some content makes us uncomfortable. I’m not sure that Imouto Paradise ever caused anybody to do any harm to others – if the law is simply about minors not being able to have it, sure, it’s an adult publication restricted to adult consumers – but I think now we’ve moved into the territory of policing what adults can consume. That to me seems dangerous. I don’t see that there’s any crime being committed, so, you know, it ends up being about policing thoughts or even taste. It’s as if Akio Nakamori was given the power to completely obliterate lolicon because he thinks that it’s gross. That’s a dangerous path.

I think if we go down that path and make any depiction of unorthodox or uncomfortable sexual relationships illegal to draw or even to think about, then we’re headed for 1984. Big Brother shouldn’t give a damn if someone reads manga about diddling his little sister. I don’t want to sound overly dramatic, but Japan has tried the whole though police thing before in the lead up to WWII and the rise of fascism. I hope that we are not seeing something similar here.

Back to the book: who is your ideal audience?

Yeah, sorry for the rant. (laughs) I hope that The Moe Manifesto is something that gets read very widely. I was very pleased to see that the cover price was keep very reasonable! I’ve done books in the past that were hardcover and cost $100, so they mostly circulated in university libraries, and I didn’t like that. Only a very few people at elite institutions get access that way. But The Moe Manifesto is just $10! It’s got a lot of content that you’re not going to anywhere else, especially the interviews with industry insiders and Japanese critics. I think that it is of interest to any fan of manga, anime and games, or Japanese culture more generally. Whether you’re on the negative or positive side concerning moe, the opinions expressed in The Moe Manifesto should challenge us all and spark new debate. Moe is nothing if not a provocative topic.