Tetsuya Akutsu stands with his hands in his pockets, an embarrassed grin on his face.

“I haven’t cleaned the place in a while,” he explains.

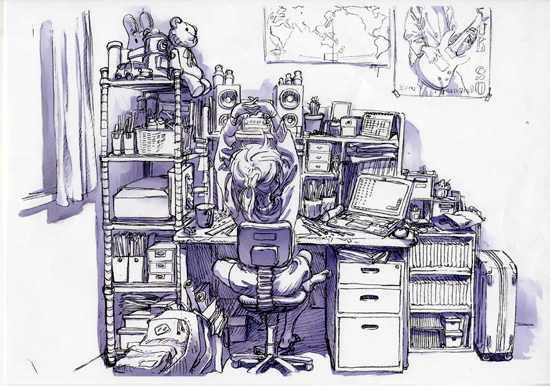

In his defense, the place, a room on the second floor of a house in west Tokyo, isn’t so much messy as it is… empty. With just a futon, a few plastic drawers and a desk, Akutsu’s room could almost be featured on one of those minimalism websites.

But looks, as the saying goes, can be deceiving: for Akutsu, an animator who works on series like Yokai Watch, this spartan room made his career possible.

“If I hadn’t been able to live here,” he says, “I don’t know what I would have done.”

A native of Tochigi, about 80 miles north of Tokyo, Akutsu was inspired to become an animator after seeing Digimon Adventure in high school. He studied animation at a trade school in Tokyo and, after graduating, was hired to draw douga – in-between frames – the first step in the career of most Japanese animators.

Douga-men (so they’re called, regardless of gender) make about ¥200 ($2) per frame. New animators can manage about 200 to 300 frames a month, meaning they take in less than $600. Not only is that less than a month’s rent in west Tokyo, where most anime studios are centered, it’s well below the city’s minimum wage.

It may sound unbelievable, but making less than a part-timer at McDonald’s is a very real scenario for many newbie animators in Japan’s anime industry.

In 2013, Jun Sugawara decided to do something about it. A CG animator by trade, Sugawara, who saw his contemporaries in hand-drawn animation struggling, created a non-profit to help support young animators make ends meet. Initially, the NPO simply provided animators a monthly stipend.

“But,” says Sugawara, “that wasn’t very interesting.”

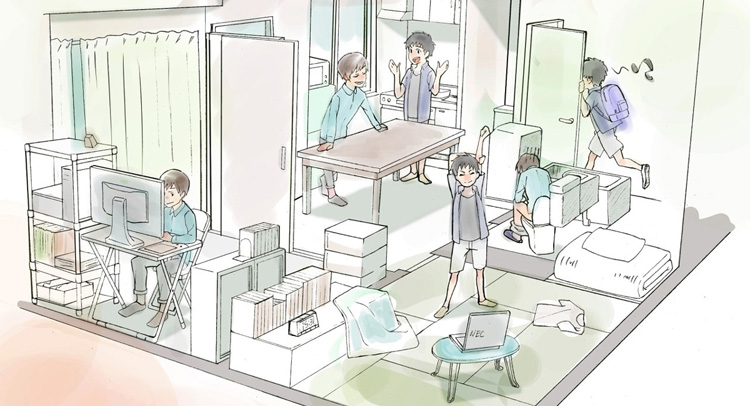

Instead, he decided to set up the dormitory, where animators could live close to Tokyo’s hub of anime studios at low cost and, just as importantly, build a community of peers.

“Most animators only know the people who work at their studio,” one animator tells me, “here we can compare notes with people throughout the industry.”

To fund the project, Sugawara used crowdfunding. Initially limited to Japanese backers, word of the project spread abroad thanks to director Sunao Katabuchi (In This Corner of the World) and North Carolina convention Animazement. Soon the project was receiving donations from America and all over the world.

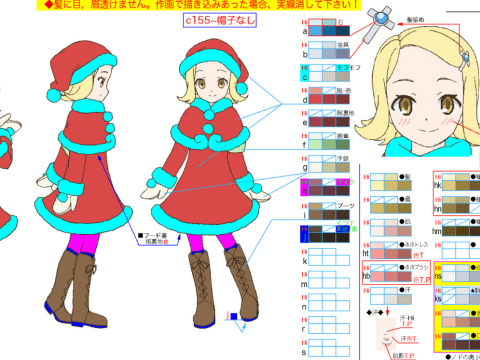

The dorm opened in 2014 with two residents and has added two a year since; this year’s additions will bring the total to eight. Potential dorm-dwellers apply via submitting a series of illustrations.

Those drawings are judged by animator Shingo Yamashita, an animation star known for his work on Naruto Shippuden and Twin Star Exorcists. Yamashita is currently at work on an original anime about a girl who transforms into a castle when she’s angry that, if successful, will provide the dorms another boost.

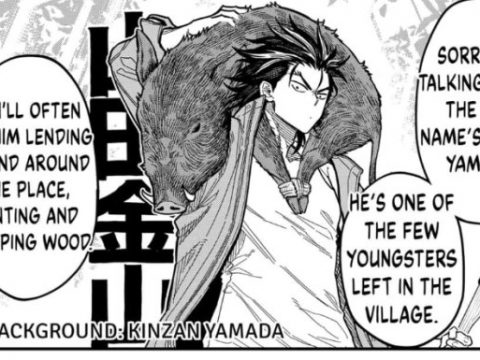

Akutsu, along with animator Masaaki Tanaka, who works at Attack on Titan’s Wit Studio, caught Yamashita’s eye, becoming the dorm’s first two residents. At the time, when the project was in its infancy, they had to share a single room. Still, they knew they had it good compared to their peers.

“Everyone who joined my studio at the same time as I did ended up quitting,” says Akutsu.

“It’s not necessarily the people with talent who stay,” adds Tanaka, “it’s the people with money.”

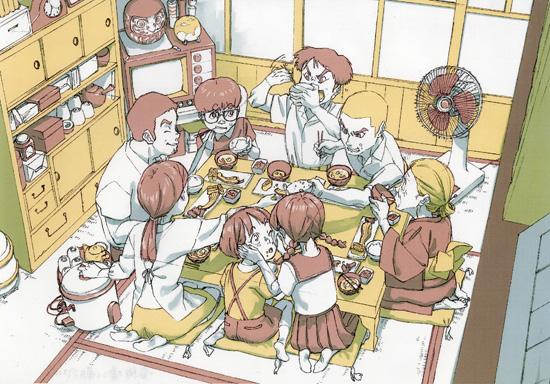

Why are wages for animators so low in the first place? It’s a complicated question, explain animators and supporters gathered at the dorm, where they meet for a group meal once a month. For one, douga artists share a problem with factory workers in Detroit and miners in coal country: globalization. Studios can pay animators in Korea and China a fraction of the cost (and, Tanaka predicts, one day they’ll even be supplanted by A.I.).

Another factor, explains Sugawara, is that even veteran animators don’t make so much money. Or, as he puts it, “the bottom is cheap because the top is cheap.” Unlike manga artists, animators aren’t paid residuals, meaning even if an anime series is a huge hit, that money doesn’t come back to the animators. Most modern anime is funded by so-called production committees, in which anime studios, record labels, game companies and other merchandisers each share a slice of the risk. If an anime bombs, everyone is insulated, but if it’s a hit, the studio itself only reaps a small bit of the reward.

Still, those at the dorm admit, some of the blame rests on the animators themselves.

“New animators don’t ask how much they’ll be making before they enter a studio,” said Akutsu, “that’s their own fault.”

“There’s been talk about forming a union for a long time,” added Sugawara, “but it hasn’t really worked out.”

But as this group of young animators sit together, swapping stories and planning their own original projects, it feels like the power to change the industry might well lie in this west Tokyo dorm.

More information about the animator dorm can be found at its official site (Japanese) or Generosity.

Matt Schley is Otaku USA’s man in Japan and e-News editor. Let him know what stories you’d like to see from Japan.