I don’t think it’s any secret that Masaaki Yuasa is one of our favorite Anime People around these parts. The auteur director behind stuff like Kick Heart, Mind Game and Ping Pong The Animation, Yuasa is the kind of unique creative talent that makes me think “yeah, anime’s still cool” on a fairly regular basis. Which is why you better believe I was excited when I found out Asuka Shinsha was publishing a massive art book on his work called Masaaki Yuasa – Sketchbook for Animation Projects (Japanese title: 湯浅政明大全).

Clocking in at a little under 400 pages, the book is stuffed with over 900 sketches, character designs and setting details from works spanning Yuasa’s career. It’s a very impressive book, made out to look like a thick stack of Yuasa’s actual spiral sketchbooks, covered in little doodles, scribbles, messily jotted personal notes-to-self, and other personal touches that make the whole thing feel like more than just another art book.

Now, the elephant in the room when talking about anything from Yuasa’s oeuvre is the weirdly inaccessible nature of it all. Though recent works like Tatami Galaxy and Ping Pong were streamed, most of Yuasa’s earlier work has ever received official distribution in the US.

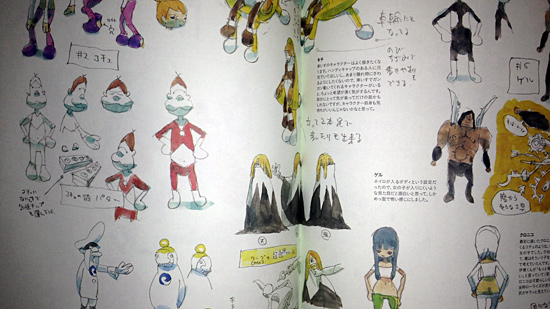

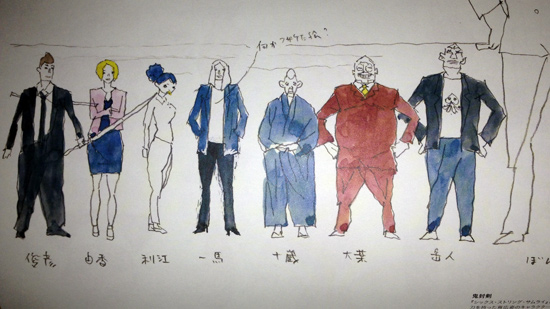

Nothing drives that home more than the first 120 pages of the book, which are all dedicated to Yuasa’s work on the movie adaptations of the long-running Crayon Shin-chan series, absolutely none of which can ever reasonably be expected to see official release in the US. That said, looking at the extremely imaginative watercolored illustrations in these pages made me want to hunt down the original movies just to get a better sense of where this guy got his start.

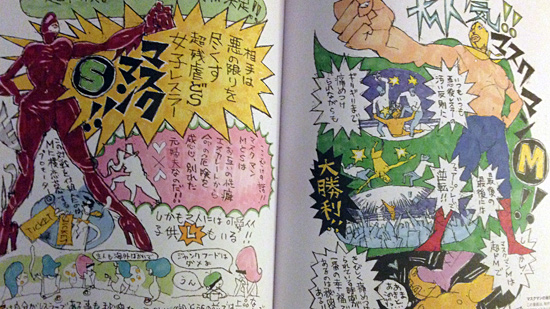

The middle half of the book, about 180 pages or so, focuses on Yuasa’s original animation projects following his departure from working on Crayon Shin-chan and move to Studio 4°C. That includes his work on 2001’s Cat Soup (which, while long out of print, did get a US DVD release over a decade ago), his 2004 movie Mind Game, along with original TV anime series Kaiba and Kemonozume, and a brief section on his Genius Party short “Happy Machine.” Rounding off the section is an in-depth look at the recent Kick Heart, which made history as one of the first Japanese animation projects to be successfully funded through Kickstarter.

The last half of the book is dedicated to smaller projects like 1992’s Chibi Maruko-chan: My Favorite Songs, 1997’s Noiseman Sound Insect, 2001’s NHK kids anime Mistin, to which Yuasa contributed dizzyingly detailed set designs. Capping things off is a reproduction of Rocket Boy, a short manga Yuasa wrote before working on Crayon Shin-chan that he wanted to turn into an anime at some point, and its follow-up from 10 years later, which both feature ideas and visuals that eventually ended up in Mind Game.

This is an extremely fascinating book to any fans of Yuasa’s work, and while I can’t provide a full translation of the whole thing for obvious reasons, what follows are a few spot translations of particularly interesting sections that caught my eye while flipping through.

On the last scene from the first Shin-chan movie, Action Kamen vs. Leotard Devil: “Originally, the last scene was a battle scene with lots of descending movement going from high to low. I always thought of ‘last scenes’ in anime movies as being about climbing to the top of something, going higher and higher.

The director, Mitsuru Hongo, asked me what I thought of it. ‘It’s not really anything special,’ I deadpanned. ‘Well, what do you think would be better?’ he asked. I showed him the ideas I had sketched out, and he liked them. Eventually, he storyboarded them into the final movie, and that scene ended up getting a lot of praise.

Up to that point, I’d never really had a chance to draw anything I wanted to see myself, and I often found myself doing the job in a kind of depressed funk. After seeing that scene animated for the first time, however, I realized ‘whoa, this is fun!’ Getting to see those images that came from somewhere deep down on a gut-level up there on the screen in motion was a supreme pleasure. And on top of that, I got to make other people happy by creating it. That was a big turning point for me. I started to get more involved with storyboarding, and eventually I found myself really enjoying the day-to-day process of working in the industry.”

On his approach to world-building for Crayon Shin-chan: Adventures in Henderland: “I drew up a complete tour of the park from the monorail. I don’t know if it all got used in the movie, but I’m the kind of person who has to draw everything that pops into their head. I need to have a grasp of the big picture in order to feel satisfied with what I’m creating.”

On his thought-process when creating Mind Game: “I thought ‘I’m making a movie, so I better make something good… or else!’ but honestly I felt surprisingly little pressure throughout the course of production. I put everything that was part of me at the time into the film. There was a scene involving music, a sex scene, fun parts, messed up parts, stupid parts, and lots of spectacle. ‘If I throw THIS much in, well… it’ll all work out somehow!’ I thought. (laughs)”

On the love scene in Mind Game: “When I was drawing out the love scene, I held a little conference with staff that probably could’ve gotten me accused of sexual harassment. (laughs) I told everyone ‘you don’t have to answer if you don’t want to, but… what kind of feeling, visually, does sex bring to mind for you?’ There were a few people who answered ‘like a bubblegum bubble popping,’ so I included live action shots of bubblegum popping. You can think of the images of birds coming to life on people’s faces and flying away in this scene as an attempt to convey feelings of exhilaration. I was pretty much playing it all by ear, but I was relieved to find that a lot of people were able to relate to the what the scene was going for once all was said and done.”

On his process when animating movement: “When I’m really into it, I sometimes find myself moving along with the characters as I’m drawing them. As I move, I start to imagine things from their perspective. If the boat passes this wave, it’s going to jump up a little bit before slowly falling. That kind of thing. It helps smooth things out when thinking about how a scene will progress. When things aren’t going to great I have to just think things through objectively, but whenever possible I try to feel things through in the moment and draw from the character’s perspective.”

On his first original TV anime, Kemonozume: “My original image for the show was some kind of tale of tragic romance, a love story about those who eat and are eaten. I had the general idea plotted out in broad strokes, but once it came time to actually make the thing I couldn’t think of ideas for the story at all. It ended up taking a while for the plot and story to really get going inside my head. Kind of a rough start.

Around the same time, I found myself really wanting to draw more adultish stuff. Kissing scenes, lascivious, slender women, that kind of thing. After leaving Crayon Shin-chan, I’d tried drawing love scenes and other risque stuff for games and the like, but I didn’t really have the chance to do anything for animation, and I found myself wanting to create something like that for discerning men and women of a reasonable age. I mean, I was in my 40s and had pretty much lost all sense of shame, so having the chance to lay it on thick with passionate kissing scenes made me pretty happy. I like to think it ended up being one of those kinda sexy, kinda scary shows kids would steal a peek at when their parents weren’t looking. (laughs)”

On “Happy Machine,” his submission for the Studio 4°C omnibus Genius Party: “I’d just finished working on Mind Game right before this, and that featured a lot of tall, lanky characters, so for this one I wanted to try drawing some rounder, squatter characters, in a simple, matter-of-fact world not unlike the one in Cat Soup. Honestly, I thought up the idea for the story in 5 minutes while sitting in a coffee shop. The theme of the omnibus was “Energy”, so I figured the other creators would create a lot of really exciting films full of fast action. In contrast to that, I decided to make something with a slower, more languid feel.

As for that I was trying to draw in this one… When you become an adult, you find yourself in an interesting position where you have to dream about protecting your children. When I was a kid, I learned how to dream from seeing the world of adults, being shown their dreams, in a sense. I thought it would be interesting to show this passing of the torch from old to young, hence the imagery in the short. Still, no matter what reality you happen to live in, the most important thing is to cultivate a mind that can feel and appreciate the beauty in the world around us. That was the idea I most tried to include in the film.”

If you’re interested in buying a copy for yourself, Amazon.jp ships books to the US. With the yen being the way it is right now, this is probably as cheap as you’re ever going to find it.

Related Stories:

– Noitamina Interviews Ping Pong Director Masaaki Yuasa

– Kick-heart Tokyo Premiere Review

– Tatami Galaxy Review

– Kick-Heart Staff Interview

– Kick-Heart Anime L.A. Interview