Talk to a Star Trek fan and chances are almost 100% that they’ve at least seen the original series from 1966 (that was nearly 45 years ago!), even if they only just recently became interested in the property thanks to the 2009 movie. Similarly, newly-made Star Wars fans still eventually go back and watch that original movie from over 30 years ago.

Anime fandom in America doesn’t work that way. We’re unique from all the others in that, on the holistic level, we have no centralized “core” group of “you have to see this” titles. This is both good and bad, but a key downside to this is that we end up having no “past.” The mega-hits of yesteryear, the things practically EVERYBODY saw once upon a time such as Star Blazers, Robotech, Sailor Moon, Trigun, and so on are not things that most anime fans now are likely to ever go back and watch on their own, even after they’ve been fans for years. After all, it is something of a universal truth that most youth generations are naturally antagonistic toward the generation which immediately preceded them. The figurative torches for these series are primarily carried by fans that “grew up” with them. They’re keeping memories of the past alive. But time has marched on; the present has shifted, and the 1990s are becoming part of “history” along with the early 2000s. As a result, yet another title fated to become part of that ever-expanding list of anime “from the before time”: Cowboy Bebop.

Jet: Back then when I got home from work, you were always there waiting for me. And that was all I needed. Just you. But on that day, when I came back home the only thing there was… a small piece of paper that had just one word written across it: “farewell.” For some reason, I didn’t feel sad or broken up. It just didn’t seem real. But slowly I realized that it WAS real; that you were gone. And little by little, I felt something inside of me go numb . . . I didn’t come here to blame you, I… I just wanted to know why. Why you disappeared like that.

Elisa: The way you talk about it, you seem to think that time really has stopped here. That’s a story from long ago, and I… I’ve forgotten about it. Time never stands still.

—Cowboy Bebop, episode 10 “Ganymede Elegy”

The above conversation may as well be talking about the overall anime fan perception of the series itself in 2010. I’ve been witnessing it with my own eyes, having conducted some informal polling over the years in which I’ve asked anime convention attendees if they’ve ever seen Cowboy Bebop. For now, almost everyone asked was at least aware the series existed, but about 40-50% of the hundreds asked were willing to admit they’ve never actually seen it. The remainder is completely shocked to find out that is the case. Chances are good that you, the reader, are having trouble accepting this as true. But in the famous words of an anime title that’s fresher in people’s minds, “believe it.” Our memories fade away over time, yes, but being “forgotten” isn’t the issue. After all, you can’t forget something that you never saw in the first place!

It’s not an issue of lack of accessibility. It’s an issue of abundance. Cowboy Bebop is not quite out of print, but with so much anime available with about as much ease as every single other piece of entertainment from competing media of both the past and present alike, how would anyone ever think to look at this series unless someone explicitly directs them? It feels like only yesterday that a recurring Internet joke was to spoil the ending of Cowboy Bebop—it was practically a catchphrase!—but you can’t actually do that anymore because it’d no longer be a joke. You’d ACTUALLY be spoiling the ending in doing so.

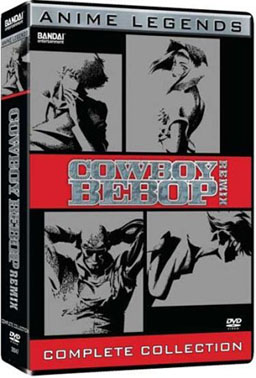

As noted in my review of the movie in Otaku USA—I’ll just assume you read that so I needn’t bother restating what this cartoon is actually ABOUT—Cowboy Bebop is now a series from 13 years ago, for which it can be honestly said that the impending DVD re-release of the movie is actually the 10th anniversary edition. Let that sink in for a minute. 1998 was that long ago! It doesn’t quite feel THAT old, does it? In the world of cartoons, you’re only “old” once people don’t remember you existed or cease to know you existed in the first place, as explained by that Tiny Toon Adventures episode with Honey and Bosko. (Oops! That cartoon was TWENTY years ago.) Cowboy Bebop is slowly but surely getting there, but it had quite the long run in America compared to most popular anime titles.

Much of Bebop’s extended lifespan in the US is owed to it gaining popularity among distinct groups of fans at different intervals, resulting in “waves”: first among VHS fansub collectors, and then a few years later with the US DVD release during a time when the DVD format was being rapidly embraced. But the single most important contributor to Cowboy Bebop’s longevity in the minds of US anime fans was the nearly-uncut Cartoon Network television broadcast and multiple rebroadcasts. As the first anime series included as part of their then-new Adult Swim block, Cowboy Bebop occupied a high-profile time slot on a popular television channel for several years. In fact, since Cartoon Network paid money for broadcast rights to that series (for most anime on TV, the US publishers pay the TV station to broadcast it), they’re actually STILL re-running it to this day… on Sundays from 2:00 AM to 3:00 AM, where few prospective new anime fans will ever see it.

In a manner akin to a US television series, the 26-episode storyline of Cowboy Bebop had a linear progression, but serialized story elements were generally not the primary focus. Most episodes were fairly standalone, which made omitting episodes from US TV broadcasts that much easier. The climax of one episode involves the usage of the Space Shuttle Columbia to save our heroes from disintegrating upon re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere. This is rather ironic, as the actual Columbia was itself disintegrated during atmospheric re-entry in 2003, and so the episode in question was pulled from television for some time. Many other episodes have plotlines related to terrorism which would be seen as particularly questionable today: blowing up high-rise buildings, committing cyber-crimes, hijacking commercial transports, waging ecological warfare, releasing biological agents upon civilian populations, and the like. I doubt we’ll be seeing cartoons with this sort of content getting near-uncut, high-profile TV airings in the near future. True, more and more of us now venture online for our media consumption, but whether you’re an anime fan who follows the pulse of what’s new in Japan by way of the Internet, a fan who watches things as they’re released on DVD in the US, or someone who watches what’s on television you stand little to no chance of ever encountering Cowboy Bebop on your own.

Like so many of the major hit anime titles in America have been, Cowboy Bebop was a series that appealed to new anime fans and non-anime fans alike. But it’s easy to forget how it managed to spark interest in LAPSED anime fans in America that were waiting for the next Akira, the next Macross Plus, the next Ghost in the Shell… and for some stalwarts, the next Star Blazers or Robotech. (And no, I wasn’t one of them; I was still 18 back then!) Here, they had it, for Cowboy Bebop was that rare breed of science-fiction: “accessible.” Unlike many anime titles, viewers weren’t expected to have knowledge of Asian culture—character names, signs, and the like were primarily in English to begin with—or have seen any other anime series prior. Certainly, pop cultural influences are plentiful and transparent, but they also weren’t the point in and of themselves. Knowing that the kid in “Sympathy for the Devil” looks like he’s Detective Conan in Lupin the Third’s original outfit, that Spike’s former associate Vicious bears more than a passing resemblance to Captain Harlock (bird and everything!), or that certain characters and scenarios are practically transplanted straight out of classic films isn’t required to understand or get what’s going on here. This is a true “gateway anime,” not just for its broad-ranging appeal, but also because it literally involves a lot of hyperspace gateways!

Said gateways are instrumental to the setting: a fully terraformed and colonized Solar System for which interplanetary travel is little more difficult than driving or flying between major cities today. This type of science fiction isn’t commonly tread-upon ground for anime. There are no exotic alien races. There is no interstellar military war. In the exact words of the series itself, “this is not a kind of Space-Opera. It is a sort of Space-Jazz which is filled with street-sense and life. This is why the central figure’s occupation is not a hero or a soldier but a bounty hunter.” Being made in 1998, Cowboy Bebop’s vision of the future less than 100 years from now—this all somehow takes place in the 2070s—is somewhat ambitious given that it was written before the year 2000 came and went without being “the future” as we’d been promised. As such, the plot is still built upon the notion of commercial space flight being feasible and commonplace in 2014, the type of thing you more or less never see in today’s SF tales which are part of what make it “dated.”

I need not implore anyone to watch this series. Either you already have and you know just how good it is and how well it holds up, or you already have decided it’ll be yet another entry on the infinite “to-do” list. Indeed, as time goes by it’ll be harder and harder to justify going back to this series.

I need not implore anyone to watch this series. Either you already have and you know just how good it is and how well it holds up, or you already have decided it’ll be yet another entry on the infinite “to-do” list. Indeed, as time goes by it’ll be harder and harder to justify going back to this series.

The legacy of Cowboy Bebop as far as Japanese animation goes is plain to see in 2010: it didn’t exactly have one. It’s not like the anime industry looked at this and responded with a plethora of spiritual successors the way that they did in response to properties like Mobile Suit Gundam, Pokémon, and Neon Genesis Evangelion. The only post-Cowboy Bebop titles that bear much similarity to it are the few other titles that Bebop director Shinichiro Watanabe has worked on since. North American anime publishers didn’t look at Bebop’s dub, which remains one of the all-time best English language anime dubs ever produced, and collectively opt to put that much time, effort, and money into everything from that point on. Instead, “faster” and “less expensive” were the top priorities. There is little we can look at in modern-era anime—production methods, setting, writing approach, action style, visual designs, you name it—and say “that element owes itself to the fact that Cowboy Bebop existed.”

The commercial interstitial eyecatches as well as the opening credits featured a few paragraphs in English regarding the creation of the bebop musical style, the spirit of which permeated into the series itself. Famously, it ended with the phrase “the work, which becomes a new genre itself, will be called… Cowboy Bebop.”

Unfortunately, it would appear that in the end, they were right about that.

This story was originally posted in December of 2010, and subsequently reposted for posterity.