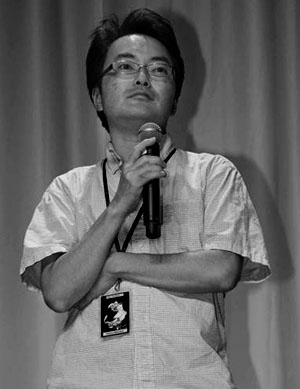

photo by Chris Gilstrap, CG Photography

Studio Kara’s Hidenori Matsubara has been working in the trenches of the anime industry for over 25 years. Chances are he’s worked on something you liked without your even realizing it. The list of his key animator credits alone is staggering: Evangelion, Patlabor: The Movie, Perfect Blue. During the 1990s, he handled character designs for multimedia sensation Sakura Taisen and was both character designer and chief animation director for the Oh My Goddess TV series and movie.

Today, Matsubara is best known for his work as key animator and animation director on the recent Rebuild of Evangelion films. He also assisted with key animation and character animation for this year’s Space Battleship Yamato 2199.

In this interview, we ask the industry veteran about the switch from analog to digital animation, tricky character designs, “Cool Japan,” and following one’s dreams.

OUSA: First things first. What inspired you to become an animator?

Matsubara: Well, I liked drawing ever since I was a kid. I grew up in Toyama prefecture, which is basically the boonies, the middle of nowhere. At the time, if you wanted to work in animation, going to Tokyo was your only option, really, so working in the industry seemed like a distant dream.

For high school, I studied industrial design at a vocational school, and at the time I wasn’t really looking to make anime or manga my career path. Going into commercial advertising and illustration was what I was in school for, and that was kind of how I expected things to play out.

Then my final year of high school rolled around, and I had to decide what my career path was going to be. One of my teachers told me “you have to follow your dreams at least a little.” That really made me think. If I gave up on my dream of going into animation, I knew I’d regret it the rest of my life, so I decided to move to Tokyo and give it a shot.

Now, that sounds like a really inspirational story, but… when I actually told that teacher I intended to go to Tokyo, he said “don’t be stupid.” He knew how difficult it was to become an animator and work in the industry.

OUSA: Was there a particular show or movie that really inspired you when you were younger?

Matsubara: The Galaxy Express 999 movie was a big one. When I saw that, I felt like… like I wanted to create something like that. Not just viewing it as a member of the public, but being involved in the creation of something like that.

OUSA: Is it true you wanted to become a civil servant at one point?

Matsubara: Just a little bit. (laughs) I wasn’t particularly serious about it.

OUSA: One of your nicknames is “Pierre” Matsubara. Where did that originate from?

Matsubara: Toei Animation made a movie when I was a kid — Puss and Boots — and I resembled the main character, Pierre. Two colleagues of mine, Hiroyuki Kitakubo and Mahiro Maeda, gave me that nickname when we went to see a re-release of the film a few years ago.

OUSA: In 1985, Royal Space Force – The Wings of Honneamise was in production. Is it true you saw the pilot movie for that and decided to take the test at Gainax to become an animator?

Matsubara: Yes. When I saw the pilot film for Honneamise, I knew I wanted to be involved, so I asked a friend of mine at Gainax to let me take the test to become an in-between animator on the movie.

OUSA: What were your lasting impressions of working on that film? Do you feel like it defined a generation? Could a movie like that ever get made today?

Matsubara: I can’t think of a work that comes close to it. Looking back, it’s just… miraculous that it was even made, that it was even greenlit. It’s unthinkable today, and it just feels amazing that Royal Space Force even exists, really.

OUSA: You’ve been there for the entire transition from traditional cel to digital animation. What’s been the biggest benefit, in retrospect?

Matsubara: This is a guess since I’m not a colorer, but I would bet that not having to wait for the paint to dry must be a huge time-saver compared to the pre-digital days.

Also, being able to deliver artwork and other animation data remotely sped up and simplified the logistics of creating a show. And of course correcting mistakes has become a lot easier.

I often hear fans of older cel-animated shows — stuff like Gunbuster, for example — wondering if the recent dearth of traditional 2D-animation for robots and the like is because the people who worked on those older shows left the industry, or if it’s simply due to how much faster it is to do that kind of animation digitally.

The animators who used to draw mecha back in the day are still around, but there are a lot more shows being made in a given quarter today, so that’s probably where that feeling comes from. Compared to how many more shows are being made, there are relatively few robot shows using traditional animation instead of CG. They’re still around, though.

I’d say the typical use for CG now would be something like cars or spaceships. Back in the 2D hand-drawn days you couldn’t really animate moving parts on something as big as a spaceship efficiently, so I’d say that’s an area where we’ve seen a huge improvement thanks to CG.

OUSA: So something like Yamato 2199, for example…

Matsubara: Yes, exactly.

OUSA: You’ve mentioned before that some shows have deceptively difficult to draw character designs. Can you offer a good example?

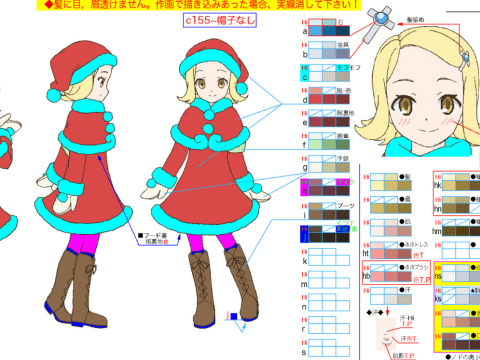

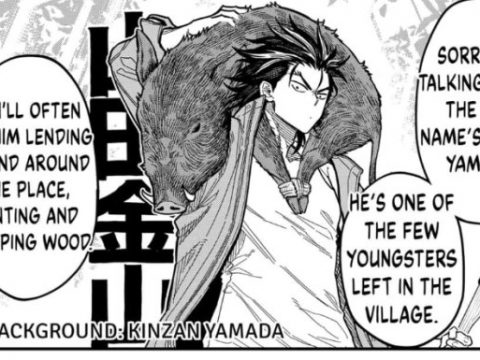

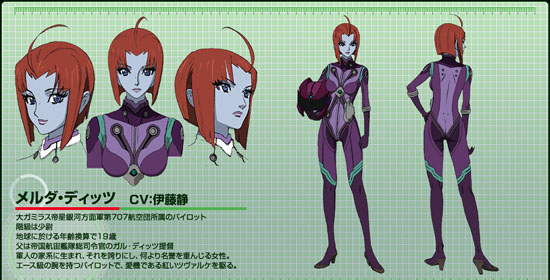

Matsubara: Yamato 2199 is definitely a good example of character designs that are simple on the surface but difficult to actually draw, and that’s something you can’t really know until you start drawing them yourself.

From 2199… There’s a character in the show named Merda who has a particularly difficult character design, I think. Her combat suit was very difficult to draw. If you look at her silhouette it’s just a simple body curve design, but actually animating it was surprisingly challenging.

OUSA: I’ve heard some pessimism from people within the anime industry about where things are going. You’ve seen everything first-hand for nearly 3 decades — what are your thoughts on the future of the industry?

Matsubara: Well, if you look at the number of titles being released, it’s always going up, right? Once upon a time there was a so-called “anime boom,” and if you look at how many shows are being made now, it’s almost double the amount that was being made during the boom period.

But in order to produce that many titles, the production schedule has been shortened pretty much across the board, and the production style has changed a lot over the years. There are definitely consequences to those kind of changes.

Many have complained about how things have changed, how the industry has changed, and how the increased production schedule and all this has become “the new normal,” and while I don’t necessarily think it’s a good thing, it is what it is and we just have to work with it.

Maybe it’s not too dissimilar from the screen acting industry, where becoming an actor is extremely hard and whether the work is fulfilling is dependent on how much passion you have for the job.

Or maybe it’s more of a business thing, and the people who feel there’s a structural problem with the industry are the business owners themselves.

%20Yuki%20Daisuke%20and%20Susumu.jpg)

OUSA: The Japanese government has been pushing the idea of Cool Japan for some time now, but a lot of writers following Japanese pop-culture in the US feel that it’s a manufactured concept that doesn’t reflect the reality of anime’s popularity worldwide. What do you think? Have you felt any impact from the Cool Japan initiative as an animator?

Matsubara: Well, I do tend to agree with those sentiments on Cool Japan, yes. It’s more of something that outsiders use to talk about Japanese pop-culture descriptively, instead of culturally, and it seems like something the government has commandeered for their own benefit. Maybe the government doesn’t actually have any idea what Cool Japan actually is, and so the push itself is the only thing that’s real.

If you look at something like the Tokyo International Anime Fair, for example… This year they had a report that compared how many minutes of animation were produced in the past year. That didn’t seem right to me. Whether or not the industry’s doing well or producing interesting content can’t be measured by simply counting how many minutes of film were made.

Even worse, the report was worded in such a way that the current year’s output was less than the previous year’s, framing it as if the industry was down from the previous year in some tangible way. That’s when I started to think Cool Japan is less about the cultural aspect of the animation industry and more about the purely industrial side.

There’s also Anime Mirai, the government initiative to train young animators by funding production on a few shows each year. Frankly, I think animators who really want to work in the industry are going to do it whether or not they have any kind of sponsorship.

There’s also Anime Mirai, the government initiative to train young animators by funding production on a few shows each year. Frankly, I think animators who really want to work in the industry are going to do it whether or not they have any kind of sponsorship.

I think it’s entirely plausible that they’ll be pushing Cool Japan more in the lead-up to the 2020 Olympics, assuming they pay attention to what they push, but just blandly bandying this idea of Cool Japan around without any thought is… I wonder if that will result in any concrete results or benfits, honestly.

That said, if some bold project were to get greenlit as a result of the initative, that would certainly be a major material benefit to the industry.

Anyway, as of right now, nothing at the studio’s changed thanks to Cool Japan, at least at the animator’s level.

OUSA: What keeps you going as an animator?

Matsubara: Well, it is work, so there’s plenty of hardships, but it’s also fun. That’s a big motivation. Creating things, drawing things… that’s fun, and the people who work in a creative industry like this are really interesting and enjoyable to work with.

You don’t get into this line of work because of the desire to make a lot of money — not that that’s a bad thing — or to get a lot of attention or respect. It really is the fun in the work that keeps you going. After all, if you’re not having fun working on a title, you won’t be able to entertain the people watching, right?