The 2010 New York International Children’s Film Festival offered U.S. premieres of three Japanese animated features from 2009—Summer Wars, Oblivion Island, and Mai Mai Miracle—all shown in subtitled 35mm prints to sold-out houses of parents and enthusiastic children of all ages. From an animation perspective, all were quite spectacular-looking and boasted great imagination.

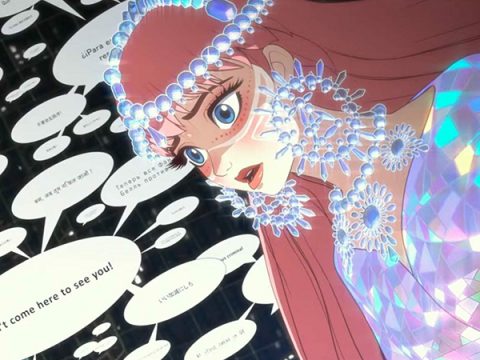

Summer Wars was done in traditional 2-D animation, interspersed with computer graphics detailing the film’s version of an internet virtual world. It was directed by Mamoru Hosoda, whose film The Girl Who Leapt Through Time played this festival back in 2007 and who also directed the second Digimon movie, the web-themed Digimon Adventure: Bokura No War Game. Madhouse Studios did the animation production.

Oblivion Island offered animation by Production I.G. and was directed by Shinsuke Sato, whose most prominent previous credit was as writer-director of the live-action swordplay film, The Princess Blade. The film was done entirely in 3-D CGI animation and uses no 2-D work at all.

Mai Mai Miracle, also produced by Madhouse, was written and directed by Sunao Katabuchi, the assistant director to Hayao Miyazaki on Kiki’s Delivery Service and writer-director of Black Lagoon and Princess Arete. It’s done entirely in traditional 2-D animation and offers a gentler, more pictorial style than the other two films and recalls the pastoral imagery of My Neighbor Totoro more than anything else.

The three films shared a number of intriguing themes and plot elements. For one thing, each of them focused on an alternate universe of some type. In Summer Wars, it’s a virtual world called OZ in which hundreds of millions of people worldwide participate via avatars who shop, sell, trade, travel, play games and engage in all sorts of other real-world-type activities. The plot revolves around a power-hungry avatar that takes over OZ and disrupts public works and transportation infrastructure in the real world (i.e. Japan). In Oblivion Island, the heroine follows a thieving fox-like creature through a hole in a fountain into a vast Wonderland-inspired underground inhabited exclusively by animal creatures who built this world entirely from human leftovers. (Their motto: “What you neglect, we collect.”) In Mai Mai Miracle, the imaginary world is actually the region of Japan where the film takes place, but 1000 years earlier (ca. 955 A.D.), when that province was home to the then-capital city of Japan, Kokuga. The heroine’s ability to visualize and “enter” the world of the past is a key plot point.

All three films also pay tribute to significant elements of traditional Japanese culture and manage to integrate them in clever ways into the modern worlds they depict. In Summer Wars, the occasion for the characters to gather is a family reunion in a small Japanese town to commemorate the 90th birthday of Granny Sakae, great-grandmother of the teenaged heroine, Natsuki, and reigning matriarch of the Jinnouchi family. The family is descended from a line of samurai, a fact we’re reminded of by all the samurai suits on display in the sprawling family house. The older characters reminisce about the days when their family was connected to the Takeda Clan and fought against the Tokugawa armies back in the 16th century. Even though the opposing Tokugawas ultimately proved victorious, the Jinnouchis developed some ingenious tactics that come into play when they’re called on to combat the evil avatar of OZ, a crafty and voracious entity called “Love Machine.”

Oblivion Island opens with a Japanese folk tale about how foxes routinely take things left out or abandoned by humans. If it’s something the owner really wants returned, they must go to a roadside shrine to pray and leave offerings of eggs to the foxes in the hopes that they will return the desired object. In the case of little Haruka, who is listening as the tale is read by her mother in the latter’s hospital room, the object is a round mirror that Haruka received from her mother and promises to always take care of. (The mirror is one of Japan’s three sacred objects.) After her mother dies, Haruka is seen leaving eggs at a shrine, first in hopes of getting her mother back and, later, in hopes of getting the mirror back. Still later, when she has entered the underground world made of abandoned objects (which carry a certain amount of metaphoric weight in Japanese folklore), Haruka seeks out the mirror and is ultimately forced into a dramatic battle with its new owner, the Baron, the self-appointed ruler of this domain.

Mai Mai Miracle takes place in the farming town of Mitajiri in 1955, ten years after World War II, and focuses on nine-year-old Shinko, who absorbs her grandfather’s every word about the storied past of the region in which they live. Shinko visualizes every detail of Kokuga and its inhabitants and the everyday life they lived a thousand years earlier. She even imagines the governor’s daughter, a lonely little princess who hungers for a playmate her own age. When Shinko meets a new classmate, Kiiko, a sheltered girl who has moved from Tokyo with her doctor father, newly assigned to a nearby factory town, she endeavors to bring Kiiko into her fantasy world. Eventually, the city girl learns to connect with the past and “see” the life of the sheltered princess, reflected in scenes of the princess leaving the governor’s mansion to visit the townspeople and give aid and comfort to a family of sick children living in a hovel on the seacoast.

All three films also deal with a loss of family members. Both Haruka in Oblivion Island and Kiiko in Mai Mai Miracle lost their mothers in childhood. We see Haruka’s mother in the early scenes of Oblivion, while Kiiko has no memory of her mother, who is seen only in faded black-and-white photos. A death in the family also figures strongly in Summer Wars.

Summer Wars and Oblivion Island both moved very fast at times and plunged the viewer into a dizzying welter of details involving their virtual/alternate worlds. To be honest, they moved a little too fast at times for this older viewer, but the children in attendance all seemed tuned into the action. Mai Mai Miracle told a slower story, with greater immersion in the textures of its rural setting, posing a threat to the attention span of the most restless kids, but it then crammed in a couple of melodramatic subplots (including a Totoro-style mad dash in search of a missing little girl) that sped up the pace considerably in the final stretch.

What surprised me was the sheer number of very young children in attendance at all three subtitled features. Either they’re child prodigies who can already read (a distinct possibility—I remember taking my daughter to subtitled films when she was quite young) or the films simply kept the audience’s interest on the strength of the visuals—another distinct possibility since all three films took great care to welcome young viewers into their alternate universes and make them feel a part of the action.

Summer Wars’ screening on opening night was graced with the presence of the film’s director, Mamoru Hosoda, who appeared on stage afterwards to field questions. Approximately two dozen audience members, from the very young to the middle-aged, all had questions for him. He took his time with each and offered encouragement to all the students and aspiring writers, artists, and animators in attendance. Some of the younger questioners were particularly astute. One boy of eight or nine asked him if Summer Wars was meant as a warning about the dangers of technological advancement. Hosoda replied that he meant to show the balance of family and technology and that if they work together, then everything can be possible.

Related stories:

– Mamoru Hosoda’s Wolf Children Premieres at NYICF 2013

– Mamoru Hosoda’s One Piece Movie

– Mamoru Hosoda’s Crayon Shin-Chan Movie

– Ghost In the Shell Director Says Hosoda “has no substance”

– The Girl Who Leapt Through Time goes live-action