The film version of Lychee Light Club opens as a group of men in dark blue uniforms chase a helpless woman through the streets, shouting in German and firing at her with guns.

But this isn’t a World War II film: as it turns out, the uniformed German-speaking men are in fact Japanese middle school boys, members of a militaristic brotherhood called the Light Club that is anything but.

The Light Club, which started out innocently enough, has mutated under the influence of its new leader, the twisted Zera (Yuki Furukawa), who forces the group to abide by a series of high-minded rules about the beauty of chess, youth and fascism.

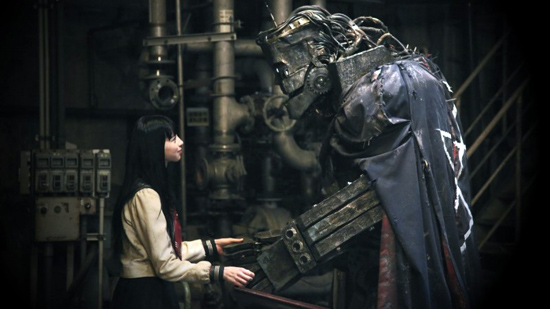

This is a bit of a farce: these are, after all, middle school boys, and what they really want is to meet girls. To that end they’ve built a hulking robot powered by lychees (the robot is named Lychee – real original, guys) to hunt down young women and bring them back to the club’s secret hideout. Lychee succeeds with aplomb, snatching up the beautiful Kanon (Ayami Nakajo). But as is so often the case, adding a girl to the mix creates new tensions, threatening to destroy the club.

Lychee Light Club, released this weekend in Japan, is the live-action adaptation of the manga of the same name by Usamaru Furuya, which itself adapted a stage play. The film is directed by Eisuke Naito, whose debut feature Let’s Make the Teacher Have a Miscarriage, another dark tale of middle school angst, sexuality and violence, made him the perfect director to helm Lychee. Otaku USA’s Joseph Luster described the original manga as “unflinchingly graphic,” and the film version doesn’t pull any punches either, splattering every conceivable bodily fluid across the screen before it wraps.

I was a big fan of so-called splatter films when I was younger, but the older I get, the harder I find it to watch humans doing violence to each other (call it empathy, something young boys don’t often have a lot of). But that doesn’t mean I think violence shouldn’t be portrayed in films – while it’s often used for pure exploitation, it can also be used to reveal things about humanity and society.

Lychee Light Club’s middle school boys seem to use violence as a substitute for sex, channeling their frustrated energy into acts of violence against the women who reject them – but also to their own bodies. One particularly gruesome scene involves lackey Niko pulls out his own eye with a spork while howling out his love for Zera. Even the sexual relationship between two of the boys is tingled with violence.

The aforementioned empathy (or lack thereof) of teenage boys also plays a huge part in the film. While most of the members take to slaughtering their victims without a second thought, the character who eventually emerges with the most humanity is none other than robot Lychee, who forms an emotional relationship with captor Kanon. It may be a take on the age-old robot-becomes-a-real-boy story, but it provides a bit of light in an otherwise very dark film.

Sexual frustration, peer pressure, idealism, hate of grownups, self-doubt: Lychee Light Club takes everything you experienced in middle school and turns the grime up to 11.

As an adaptation, Lychee Light Club does fairly well – that is to say, it doesn’t feel, like some manga or anime-turned-live-action films do, like the actors are glorified cosplayers. That’s likely because the manga itself was based on a stage play. But ironically, this hurts Lychee as a film, because most of the movie takes place on a single set, and the actors play their roles with that oversized version of acting better suited to the stage than to cinema.

I’m not sure I liked Lychee Light Club – that seems like the wrong word for such a dark, grotesque film – but certainly succeeds in being a stomach-turning exploration of the male middle school experience, and that’s something.

And I’m not sure I’ll ever eat another lychee again.

Matt Schley is Otaku USA’s man in Japan and e-News editor. Send him a tweet.