Way Out

Truth be told I was a late convert to the church of anime director Kunihiko Ikuhara, and even now consider myself something of a skeptic. While I’ve since come to appreciate his unbridled artistry and technique as well as his utterly unique narrative voice and daring decision making, for ages I responded as any other detractor might: I found his reliance on symbolism to be offputting bordering on obnoxious, found his tendency to moralize didactic bordering on condescending, found his campy sense of humor arch bordering on precious, found his psychoanalysis of his characters to be reductive bordering on pat, even once or twice lobbed the lazy insult of “pretentious” his way.

It was the wrong response, but not necessarily wrong-headed. After three viewings the central conceit, Yurikuma Arashi still feels muddled and uncertain due in no small part to its setting and backstory, while it’s only in the late stages that the Utena series take on a narrative urgency and humanity that often feels hampered by the early episodes’ rigid formula and structure. Only Mawaru Penguindrum I can recommend without reservation because it’s only Penguindrum with its decisions to tackle the ugly realities of post-Bubble and contemporary Japan that feels immediately relevant, less like a morality play staged by a talented and superior teacher than an urgent but deep-hearted warning from a friend stuck in those same trenches.

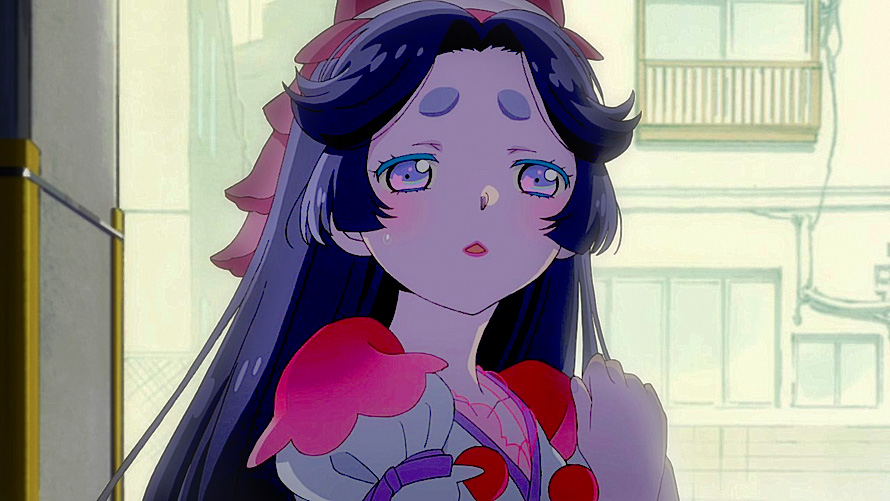

Sarazanmai feels similarly pressing. Not in the same way, no: it’s a far bawdier production than Penguindrum, packed with jokes about butts and a thousand ass-flavored visual cues and puns all built around a central conceit that has adolescent boys Kazuki, Enta, and Toi transforming by night into kappas the better to extract the mythical shirikodama that lie nested in the anus of recently departed zombies. The theatrical stylings that dominated Yurikuma and Utena are on full display here, too, as no zombie can be created without a Bon Dance from two glamorous authoritarian Otter Cops, no shirikodama can be plucked without a full-blown musical interlude from the heroes, nor any secret processed without a figure skating routine that brings the three boys into a perfectly synchronized pattern that also not coincidentally synchs their thoughts and reveals their deepest secrets.

It’s absurdist in ways that Penguindrum only ever flirted with, leaning as far into its most outrageous ideas without apology or restraint. Nobody could accuse Ikuhara of shying away from camp or paying mere lipservice to the queer cultures he cribs so much of his iconography and imagery from, but before Sarazanmai it never felt so raucous or raunchy: it takes only minutes of the first episode before the main trio are ejected from a rectum and covered in brown-tinted juices.

Yet while Sarazanmai can trace its obvious visual and aesthetic debts more easily to Utena or Yurikuma, like Penguindrum it’s set not in some fairy tale academy or proxy world besieged by perpetual ursine warfare but grounded in contemporary Tokyo. Characters spend their days waiting on a fresh shipment of boxes from obvious Amazon proxy Kappazon while a famous idol reads out the morning news from massive central screens like a post-modern Greek chorus; between classes students take time to browse social media services or stroll over to Asakusa for a celebrity signing. Even the more absurd elements of the story are marked by contemporary signifiers: wi-fi waves denote the connection experienced by the boys each time they retrieve another desire; the Otter Cops, for all their absurdity, still find themselves affiliated with the more mundane, forward-facing police department they represent the shadowy underside of. The bodies they leave in their wake as they attempt to “harvest desire” are no mere metaphor but actual human costs.

And, indeed, its exactly this actual human cost that Ikuhara is particularly concerned with here in Sarazanmai as he explores the ways contemporary Japan’s various structures of authority and seclusion seek to isolate us from our neighbors as well as ourselves. Boxes have always been a prominent visual motif and pointed metaphor in Ikuhara works symbolizing the ways we partition ourselves off—recall Doctor Sanetoshi’s lament that people “bend and stuff their bodies into boxes…” the better to fit society’s constraints—but it seems especially telling that here in Sarazanmai the boxes the heroes each store their secrets in are labeled (as is every other box in this world) Property of Kappazon. And that these same Kappazon containers are the ones the Otter Cops consign their victims to when their desires have been extracted and they’ve been disposed of. As if to say that the systems of authority supposedly intended to protect us and the systems of commerce intended to sate our longings in fact work in concert the better to divide us from our deepest desires and subsequently not only our own sense of self but our connection to others.

It is secrets—and more particularly secret desires—that the main trio are tasked with extracting from the shirikodama, and it is secrets that they inevitably share upon synching up after each successful extraction. Whether it be the knowledge that Enta stole a kiss from the sleeping Kazuki or the revelation that Toi first killed a man in childhood, these late night escapades to retrieve the knowledge of others seems destined to bring together three young men who feel great reason to hide themselves from the larger world and from those they love most but with the implication that any such knowledge carries extensive costs. In a world where connection between people becomes ever more abstract even as they become ever more entwined and so identity becomes ever more porous but also more carefully pruned and guarded such a work seems only the more urgent.

It’s early days yet, of course, with only four episodes aired at the time of this writing, but the effect Sarazanmai achieves by locating its action in our own world and time is something of weight, of physicality, an invaluable trait for a story that lets viewers forget neither the humor nor tragedy inherent in their own physical state. Connection may be a painful and too often uncomfortable experience that invites us to risk humiliation and derision, elements a series as unabashedly absurd as Sarazanmai likewise invites us to risk. It seems a small chance to take for something so fresh, so novel, so bold and strange and rewarding.

Sarazanmai is available from Funimation.

This story appears in the October 2019 issue of Otaku USA Magazine. Click here to get a print copy.

![SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review] SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/16-9-SSSS.Dynazenon_Key_Visual_3.5-480x360.jpg)

![Back Arrow [Anime Review] Back Arrow [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ba15-02686-480x360.jpg)

![Dawn of the Witch [Manga Review] Dawn of the Witch [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/16-9-DawnoftheWitch-cvr_02-480x360.jpg)

![Nina The Starry Bride [Manga Review] Nina The Starry Bride [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/nina-the-starry-bride-v1-16-9-480x360.jpg)