Junya Inoue is best known for his character designs and artwork for shooters by famed Japanese developer Cave—from DoDonPachi to Deathsmiles—as well as his manga, Otogi Matsuri. We sat down to discuss everything from the beginnings of his storied career in games to his latest manga project, BTOOM.

Junya Inoue is best known for his character designs and artwork for shooters by famed Japanese developer Cave—from DoDonPachi to Deathsmiles—as well as his manga, Otogi Matsuri. We sat down to discuss everything from the beginnings of his storied career in games to his latest manga project, BTOOM.

* * *

When did you first take an interest in drawing?

I don’t remember exactly when, but there’s this sketchbook full of crooked Ultramen that I drew when I was four at my parents’ house.

Who would you say were your biggest artistic influences?

It’s hard to decide who was the biggest influence, but I loved building plastic models of Mobile Suit Gundam, and drawing their designs as a child. Thinking about it more in-depth, I really think it was Mobile Suit Gundam that made me realize how much fun drawing is.

So, if I have to choose one, it would be Yasuhito Yoshikazu … Or maybe Kunio Ohgawara? (the designer of Gundam)

How did you wind up getting into the games industry? Was that your original career intent?

It was quite a shock when I first saw Ghosts ‘n Goblins at an arcade when I was fourteen. That was when my arcade days began. Ghosts ‘n Goblins was an action game, but it had plenty of shooter elements (I was into shooters as well).

When I was first looking for a job back in 1991, I found a recruitment ad for my favorite game development company (Toaplan) in a game magazine (GAMEST), so I made a phone call for an interview. It was my ultimate goal to change someone’s life with something I created back then.

You began your career at Toaplan, a developer well loved and regarded by fans of late-80s/early-90s arcade games. What was the corporate culture at the company like? Do you have fun stories to share about your time working there?

The general atmosphere at Toaplan was pretty much “anything is possible,” symbolizing the booming economy in Japan at the time. We often did crazy things. New staff would have to perform some party trick during a year-end party each year, but if the trick was boring, older staff would use a fire extinguisher on them… A bunch of us would go to a restaurant, and compete with each other to see who would be the first to finish all the almond jello. The winner would throw up the almond jello, and leave the restaurant… I have to admit that we behaved pretty badly whenever alcohol was involved. *laughs*

Did it ever become apparent that Toaplan was in trouble? Did this effect the work environment at all? What do you think was the primary cause behind the company’s dissolution?

Did it ever become apparent that Toaplan was in trouble? Did this effect the work environment at all? What do you think was the primary cause behind the company’s dissolution?

I was still one of the new members of the company, so I’m not sure exactly what happened, but I once heard from my supervisor that it was because we made Yama mad. *laughs*

Can you tell us a bit about the next company you worked at, Gazelle, and what happened there?

A couple of us Toaplan staff (most of them were from the BATSUGUN team) were selected by our boss to be transferred to another company, which turned out to be Gazelle. We weren’t able to quite get along with Gazelle staff, so we eventually left the company one by one. I don’t know much about it, but there were some scary rumors going around back then… *sweat*

How did you come to join Cave after that?

One week after I had left Gazelle, I was given an offer from Mr. Ikeda (my senior from Toaplan) of Cave to join the company. I had another offer from RAIZING at the time, but since I had always looked up to Mr. Ikeda for his passion toward game making since I was involved in the BATSUGUN team, I decided to join Cave to make games with him.

What was your first project at Cave?

It was DoDonPachi for arcade. Since I joined the team in the middle of its development process, I only supported the team for the story part and the bee boss in the last stage.

One of your most well-known works for Cave is ESPrade. What was development like on this title?

Since it was my first project as a graphic director, I wanted to make the game that could visually attract consumers. But, since the budget for arcade shooters wasn’t very high at the time and the hardware spec that we were using was way below the market standard, I had to first figure out what was the best possible product we could make under those conditions. I experimented with 3D rendering, Photoshop, and such while testing what could and couldn’t be done throughout the development process. It’s like building something, and revising a blueprint for it at the same time. Nobody knew what kind of game it would turn out to be at that point.

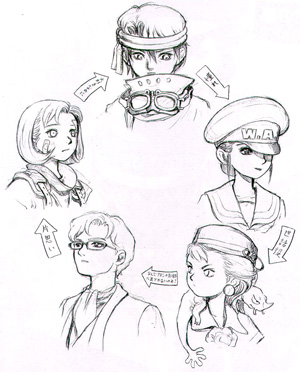

Some elements seen in early design documents for ESPrade didn’t appear in the final game. Can you tell us about what didn’t make the cut and why?

Some elements seen in early design documents for ESPrade didn’t appear in the final game. Can you tell us about what didn’t make the cut and why?

I usually draw whatever pops into my head when I first design something. Then, we select whatever might work for a certain project from those drafts. As this process continues, both the number of ideas that weren’t accepted, and ideas that are more effective increase, changing the initial image of a certain game. It’s like planning ahead before you travel. You would normally create a list of things that you want to do at your travel destination, but if you discover something you didn’t know before while you’re there, your original plan wouldn’t go smoothly, would it? But, the thing is that there’s also a chance that it might lead you to something good that you never expected.

One of your later works, the manga Otogi Matsuri, has characters that bear a very strong resemblance to the ESPrade cast, down to similar names. Is this intentional? Does Otogi Matsuri feature ideas you couldn’t use in the final product of ESPrade?

I want to say it does. One of the basic concepts for Otogi Matsuri was to adopt ideas that weren’t feasible for games in general. Emphasizing stories in arcade shooters would affect sales in a negative way, so we needed to tone it way down so that it would only be an “extra spice” on top of the main game. It was fine for what it was, but I was so desperate to give life to those ideas that I even quit the company to make my dream come true. It took me six years to finish it, but that six-year period was filled with new discoveries about myself and new possibilities.

What are your thoughts on the follow-up ESPgaluda series?

I think it’s fine for what it is… I still feel the term “ESP” doesn’t go very well with its lore (the “world view”), though.

Guwange is another popular title you worked on. Again, I see similarities to Otogi Matsuri in the design of the monsters. It seems as though you have a very strong interest in Japanese mythological monsters. Where does this fascination stem from?

It must stem from my childhood background. I was raised in a country town where the ancient concept of Yin and Yang was deeply rooted in our lives. I had never realized the uniqueness of the environment where I was raised until I moved to Tokyo. I didn’t initially take an interest in Japanese-style things, but it must’ve been deeply rooted in me since I was a child. I realized how much I like things that are originated in Japan when I started on Guwange. And, by things that are originated in Japan, I mean the Way of Yin and Yang and Japanese mythological monsters rather than samurai, ninja and such.

Guwange is seeing a re-release via Xbox Live Arcade. Are you doing any new work for the game?

I’m not doing anything particular for the game. I was pretty much swamped with Deathsmiles IIX. *laughs*

Progear was a collaboration between Cave and Capcom. What was it like working with a new partner on new hardware? Were there any significant challenges to overcome?

The biggest challenge for the project was to figure out how we should convince users that it’s a new game while it had a far inferior basic spec to the version used for Guwange. I don’t think it was much of a challenge for the programmers, but we designers had a very difficult time with it. We would use 16 colors to re-draw drawings that were already created in full color with Photoshop—this was a process that was required. It took twice as long as Guwange.

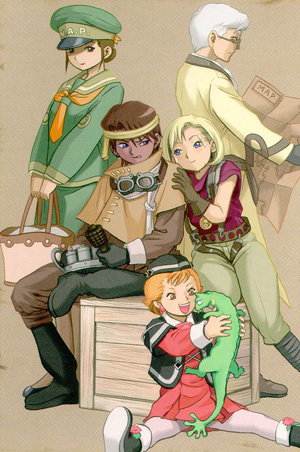

Children and teens as lead characters seem to be a common theme in the games you work on, perhaps seen most prominently in ESPrade, Progear, and Deathsmiles. Is there a reason for this?

Children and teens as lead characters seem to be a common theme in the games you work on, perhaps seen most prominently in ESPrade, Progear, and Deathsmiles. Is there a reason for this?

I just love the idea of kids fighting against evil. There’s no other reason to it!

While you were working at these various game companies, you were also active in the production of doujinshi and doujin items. Was it difficult to balance your work art obligations with your doujin production? Did your employers have any objections to your side hobby? (Incidentally, I’ve been looking for your doujin for ages and have yet to find any in the used shops in Japan that I have searched. Either you really produced in low numbers, or everyone loves you work so much that they don’t resell it!)

I must’ve started involving in the production of doujinshi because I wanted to become a cartoonist. I wanted to do more than just designing games. The reason you couldn’t find any print runs had only 1,500 copies printed.

One of your more obscure works is the PS2 skating game Yanya Caballista. How did this title come to be? What sort of work did you do on it? Were you disappointed that it didn’t perform so well on the market?

I joined the team as a director in the middle of the development process. It felt like I was asked to take helm of the ship that had already struck a rock. We had the craziest schedule for the project where the only thing that was implemented in the game at the time were the button controls, and yet we only had one more month before an alpha ROM submission. We started designing the best possible game system we could manage, utilizing whatever that was done at the time, then created stage layouts and items specs. We managed to make it a sellable game in half a year, but it was like the hardest time of my life.

A little while after Yanya Cabillista came out, I recall reading in your blog that you had become disillusioned with the game industry, and that was part of the reason you had left Cave. Do you still feel this way, or have circumstances changed since then?

It was more of a disappointment where I realized there was a limit to what I was capable of in the game industry. This is going to sound depressing, but after the launch of PS2 the cost of game development skyrocketed. It started a trend where only solid series, licensed games and monumental games developed by capable teams became prominent in the market. I lost hope when I realized that Yanya Cabillista was the best I could do at Cave, even though I gave it 120%. When I thought about the hardships other game developers must be going through, the idea of quitting the company to become a cartoonist came very natural to me.

You’re currently a freelance artist, but your primary output these days is manga. How is manga production similar to doing artwork for video games? How is it different? Do you find it more or less stressful?

Doing artwork for video games is similar to manga in a way that both create a world. Video game artwork is different from manga because the smallest details of video games are up to programmers. I feel this way probably because I was only involved in graphic designing part of game development. In manga, on the other hand, I can adjust dialogues however I want until the last minute before sending a manuscript, which is normally a programmer’s job for video games. I can get a solid sense of interaction with consumers with manga. That’s why I think manga is way more challenging to make than video games.

How did you come back to work with Cave for Deathsmiles? How much of the story and setting of the game is your own design?

I took care of almost all of the story and designs of the game. When I looked at shooters released by Cave as an observer after I had quit the company, the graphics, characters and programs didn’t seem in sync. This is just my personal opinion, but it felt that they were completely uncoordinated… It was frustrating to see them struggle, so I tried and put together a proposal for a game called Deathsmiles.

It seems like these days—especially with the success of Touhou—shooters have moved away from the mechanical and superhuman themes of the 80s, 90s, and early 00s to become dominated by “moe” aesthetics. Do you like this shift in design? Why or why not? Do you think “moe” is a fad, or will it be pervasive for years to come?

It seems like these days—especially with the success of Touhou—shooters have moved away from the mechanical and superhuman themes of the 80s, 90s, and early 00s to become dominated by “moe” aesthetics. Do you like this shift in design? Why or why not? Do you think “moe” is a fad, or will it be pervasive for years to come?

I quite don’t get the concept of “moe” myself, but based on my current knowledge, I think it will continue spreading, and finding its audience. Those who are into “moe” because it’s a fad might get bored with it soon enough, but those who are selected by “moe”… I think it will be deeply instilled in their minds like a religion.

On that subject, where do you see the shooting game genre going from here? How about video games in general?

The shooter genre seems a little outdated as far as I’m concerned. I once tried to convert ordinary shooters to 3D out of a sense of mission fifteen years ago, but it never made a break with 2D. With a declining birthrate and aging of shooters… I’m afraid that the shooter can no longer attract new audiences in Japan. Sometimes I feel that this, one of the oldest game genres, can attract new fans abroad. I occasionally find myself having fun fantasizing that it could be a boy from India who is the world’s No. 1 shooter player someday.

Finally, can you tell us a bit about your latest comic, BTOOM?

If Otogi Matsuri represents the ideas that I have become aware of in the game industry, “BTOOM” would represent the experiences themselves that I went through in the game industry. I expect BTOOM to be completely different from Otogi Matsuri in terms of designing. I intend this to be an entertainment for adults, so those of you who are middle-aged men, please look forward to it.