Fairy tales are fearsome and cruel. Don’t let the Disney-fied versions fool you; the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen penned little morality plays that had all of the subtlety of a mace to the face and all of the delicacy of an abattoir. And this literary tradition is not limited to Europe; all of the nations of the world have their stories designed to cow impressionable children into straightening up and flying right.

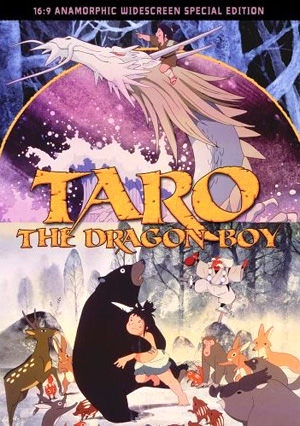

One of those tales is the Taro the Dragon Boy.

I don’t want to give the wrong impression; I don’t mean to imply that nothing magical or wondrous happens in this 1979 film from Toei studios. On the contrary, Tatsunoko Taro, aka Taro the Dragon Boy, overflows with examples of fairy tale logic: A butcher’s cleaver thrown into a stream transforms into a carp and swims away. After winning a sumo match against a tengu, Taro drinks a cup of sake that gives him the strength of one-hundred men, but only when he turns his efforts to helping others; when his superhuman strength activates, Taro’s body blossoms bright red in a drunken flush. Later, Taro defeats a monstrous black oni by tickling it into submission and tossing it off of a cliff; the oni turns to stone upon impact. Wild animals converse with their human friends, and an exceptional pony can run across thin air when it reaches maturity. The film is a wonderland of make-believe.

But fact tempers fantasy, and beneath and throughout the plot of the film—which centers around Taro trying to find his lost mother, who has been cursed with the body of a dragon—there runs a theme that is grounded in the truth apparent to a culture eking out an existence on a chain of volcanic rocks in the middle of the Pacific ocean. What the fanciful story of Taro the Dragon Boy is really about is the reality of famine and the politics of hunger.

Consider the protagonist: Taro begins the story as a typical oafish lout in the style of the Monkey King. He is lazy and gluttonous; instead of helping his grandmother and the other villagers to farm, he spends all of his time sleeping, stuffing his face, or playing with the animals of the mountainside. All this begins to change when he sets out on a quest to find his mother; in between encounters with various monsters and spirits, Taro slowly realizes how hard life is for the farmers that till the earth. Often their bodies are naked and their fields are bare. During his travels Taro learns how to cultivate and harvest rice, which he shares with the peasants he meets. He uses his great strength to crush boulders and reroute rivers to aid in irrigation. Eventually, his quest culminates in a heroic act of selflessness in an effort to free his mother from her curse.

And what brought about this curse in the first place? What grievous transgression did Taro’s mother commit to prompt this monstrous transformation?

When she was pregnant with Taro, she ate three fish.

Sounds harsh, doesn’t it? But the message here is that her appetite left others with nothing to eat while she gorged on the food meant for everyone. It’s the same realization that strikes Taro when he first tastes cooked rice; he can’t savor the flavor, because he knows so many of his loved ones have nothing to eat. It’s a harsh lesson, but a valuable one: share or perish, work the fields together or starve alone.

When I purchased Taro the Dragon Boy over five years ago, I didn’t know what to make of it. The film is beautiful and strange and troubling. In some sense it feels like a Walt Disney film, if Disney didn’t whitewash the morals of his source material and turn their messages childish and simplistic. And it looks in some sense like The Last Unicorn, with gorgeous backdrops that range from the desolate to the surreal. But the film’s execution is so fundamentally Japanese, from the themes to the setting and the creatures and people that populate it, that it can be difficult for a foreign viewer not saturated in the nuance of Japanese culture to swallow. And whether it’s Taro’s groin-exposing handstands or the lascivious groping of yama-uba and yuki-onna or the stylized violence of the finale, there are parts of the movie that leave me scratching my head. Though I am older and wiser, I still don’t know what to do with Taro the Dragon Boy.

When I purchased Taro the Dragon Boy over five years ago, I didn’t know what to make of it. The film is beautiful and strange and troubling. In some sense it feels like a Walt Disney film, if Disney didn’t whitewash the morals of his source material and turn their messages childish and simplistic. And it looks in some sense like The Last Unicorn, with gorgeous backdrops that range from the desolate to the surreal. But the film’s execution is so fundamentally Japanese, from the themes to the setting and the creatures and people that populate it, that it can be difficult for a foreign viewer not saturated in the nuance of Japanese culture to swallow. And whether it’s Taro’s groin-exposing handstands or the lascivious groping of yama-uba and yuki-onna or the stylized violence of the finale, there are parts of the movie that leave me scratching my head. Though I am older and wiser, I still don’t know what to do with Taro the Dragon Boy.

Distributor: Discotek Media

Originally released: 1979

Running Time: 75 minutes