A young college student falls for a quiet, mysterious boy in class. They spend time together, growing closer, until one day he reveals his secret: he’s half-wolf, able to transform at will. Instead of being afraid, the girl, Hana, embraces his difference, and soon they have two children, Ame and Yuki, both also able to transform into pup-sized wolves.

One day shortly after Ame is born, Hana’s wolf-man doesn’t return from work. She goes searching, eventually confirming her worst fear: mistaken for a wild wolf, he’s been killed. Now a single mom of two half-human, half-wolf kids, Hana moves her family from the prying eyes of the city to a farm town, where her children can lead relatively normal lives – or so she hopes.

So begins The Wolf Children Ame and Yuki (Okami Kodomo no Ame to Yuki), the third major film from Mamoru Hosoda, director of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and Summer Wars. Hosoda is frequently cited as the next Hayao Miyazaki, and Wolf Children does nothing to dispel that notion, building an atmosphere that feels distinctly Ghibli-esque, both in terms of setting and characterization. In this way, Wolf Children is a qualified success: a very well-made film, but one that doesn’t feel particularly fresh.

Though rooted in a supernatural situation, Wolf Children is essentially a family drama, and a quiet one at that, more interested in portraying the small struggles of familial life than any overarching conflict. With its subdued humor and atmosphere, the film is more The Girl Who Leapt Through Time than Summer Wars. Or, using the inevitable Studio Ghibli comparison, it’s more Isao Takahata (Grave of the Fireflies) than Hayao Miyazaki.

Japan is increasingly made up of “mixed” families, in which one of the parents comes from another country. The children of these families are referred to as “half” (i.e. half-Japanese, half-foreigner) and in as homogeneous a society as Japan’s, “half” children can have a hard time finding their place. It’s possible to see The Wolf Children as an allegory for this issue. If so, it seems to contain the somewhat depressing message that “half” children must eventually choose one of their two sides, as Ame and Yuki discover as the film progresses.

As much as it is about mixed-heritage children, Wolf Children is also a story of single motherhood. In an interview, Hosoda mentioned his admiration toward new mothers as one of the driving factors in making the film, and that admiration is clear in Hana, who is unfailingly upbeat and encouraging in the face of her unique situation. That determination and self-sacrifice make her the emotional center of the film, balancing the sometimes prickly Ame and Yuki, who like any young adults (and especially ones who can transform into wolves) have plenty of physical and emotional growing pains.

Visually, the film is charming, retaining the super-flat, non-shaded style of Summer Wars. Less frenetic than Summer Wars, Wolf Children spends more time giving us lush, photo-realistic landscapes. It also displays the industry’s ever-increasing reliance on CG animation: both crowd shots and effects like waterfalls and plants move in a distinctly computer-generated way. As with many other anime films, the CG and the hand-drawn don’t always mesh, and the results are occasionally distracting. Largely, though, Hosoda doesn’t let the visuals distract from the story, usually choosing to place his characters squarely in center frame.

With films like last year’s Children Who Chase Lost Voices, this spring’s Letter to Momo and now The Wolf Children Ame and Yuki, it’s clear major anime studios are placing their box-office bets on properties that clearly evoke the works of Studio Ghibli. With no clear successor to Miyazaki and Takahata yet to emerge at that famed animation house, it seems their legacy will remain intact, albeit perhaps at other studios. One wonders, though, if in Hosoda’s case, the continuous Ghibli comparisons are becoming a burden, keeping him from breaking free and finding his own voice.

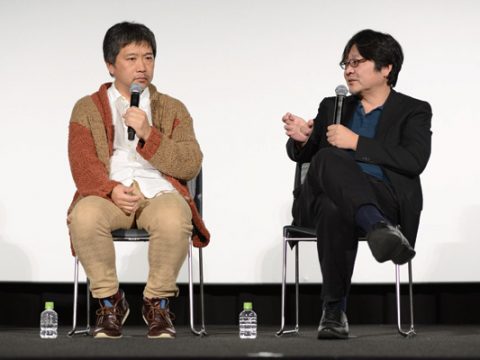

Don’t miss our exclusive interview with Mamoru Hosoda from NYICF, as well as our transcript of his Q&A session. For more NYICF, see our report on NYICFF 2010, where Mamoru Hosoda’s Summer Wars premiered.